TELEMEDICINE ADOPTION AND DIFFUSION: THE CASE OF

THE UNITED ARAB EMIRATES

Nabeel Al-Qirim

College of Information Technology, United Arab Emirates University, P.O Box 17555 - Al Ain

United Arab Emirates

Keywords: Telemedicine, UAE, Cases, National strategy, telemedicine networks, Mayo Clinic, Abu-Dhabi, Al-Ain.

Abstract: This research was initiated to explore telemedicine (TM) adoption and diffusion in healthcare organizations

in the UAE. According to the exploratory findings of this research, the research endeavored to achieve two

main targets. Initially, it was revealed that the telemedicine phenomenon was not that extensive in the UAE

in the sense there was no self initiated TM networks or specialty TM centers as such. According to this

finding the researcher attempted to explore the perceptions of healthcare professional in the UAE about their

attitudes and behavior towards adopting the TM technology in their organizations using a theoretical

construct extended from the technological innovation literature. Secondly, the existing TM initiatives in the

UAE were initiated in cooperation with Mayo Clinic to have complete multimedia TM system for tele-

consultations (second opinion). The effectiveness of this approach is also examined in this research. The

research discusses the research findings in the light of the overall literature highlighting further implications

and suggesting ways where TM could be pushed forward in the UAE. What is yet to be seen in the UAE

context is the initiation of self governed specialty TM systems and networks.

1 INTRODUCTION

Telemedicine (TM) means medicine from a distance

where distant and dispersed patients are brought

closer to their medical providers through the means

of telecommunication technologies (Charles, 2000;

OTA, 1995; Noring, 2000; Perednia & Allen, 1995;

Wayman, 1994). TM can assist in reaching out to

rural patients (Charles, 2000; Harris, Donaldson, &

Campbell, 2001) and to areas where patient volumes

for certain services are limited (Edelstein, 1999). It

can also assist in implementing administrative and

clinical meetings (i.e., journal discussion, case

discussion), in providing different health-awareness

courses to patients (smoke treatment centers), in

delivering training courses to physicians (discussing

research journal), nurses, and other medical staffs

(Perednia & Allen, 1995; Wayman, 1994), and even

to a level where telemedicine could be used to

promote disease prevention, lifestyle management

and well-being (Lemberis & Olsson, 2003).

TM covers a wide spectrum of benefits in

healthcare through the use of TM utilizing the video

conferencing technology in areas such as

consultations, diagnostics, therapeutic, transfer of

patient related records, case management, training,

and meetings. This mounting hype amongst

researchers and practitioners about TM advantages

lead to a conclusion that TM could be an essential

building block in the strategic plan of many

healthcare organizations (Charles, 2000). In a rural

setting, TM could help health providers in supplying

quality, fast, and economical medical services to

patients including rural ones and hence, saves

doctors and patients valuable time wasted in

commuting large distances (Oakley et al., 2000).

Specialists could utilize this extra time in seeing

more patients at the main hospital.

1.1 Telemedicine in the UAE

Medical services in the UAE has improved

dramatically during the past 30 years where the

number of hospitals increased from 7 to 30, the

number of beds increased from 700 to 4473 and the

number of primary health care centers increased

from 12 to 115 (MOH1)

In the UAE, the term telehealth and TM is not

widely recognized as such. In scanning for

telemedicine initiatives within the UAE, to the best

191

Al-Qirim N. (2006).

TELEMEDICINE ADOPTION AND DIFFUSION: THE CASE OF THE UNITED ARAB EMIRATES.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on e-Business, pages 191-199

DOI: 10.5220/0001426001910199

Copyright

c

SciTePress

of the author’s knowledge, the following

organizations were the only ones reported to adopt

telemedicine projects and applications:

i. Tawam hospital.

ii. Mafraq Hospital.

iii. UAE University (UAEU):

iv. Higher Colleges of Technology (HCT).

The first two are hospitals in the Emirate of Abu

Dhabi and the last two represents an educational

institution. The UAEU has a Faculty of Medicine

and Health Sciences (FMHS) in Al-Ain city and the

HCT provides health-related courses and degree

nationwide.

Given the above stocktaking of the above TM

initiatives in the UAE, it is important to investigate

the potential importance of the TM technology in the

above cases. Therefore, this research attempted to

achieve the following objectives:

i. what are the adopted TM technologies in

these institutions.

ii. where they are being used.

iii. reasons for adoption

iv. challenges facing TM adoption and usage.

v. Extent of adoption and usage of TM.

In the following the research will introduce the

theoretical framework followed by the research

methodology. This is followed by a description of

the cases and the adopted TM technologies. The next

section will show analysis across the different cases

followed by a discussion and a conclusion.

2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

In search for a guiding theoretical framework that

could assist this research in explaining factors

influencing TM success, the classical innovation

diffusion theory (Rogers (1983; 1995) model)

appeared to be the most widely accepted framework

by researchers in identifying critical characteristics

for technological innovations (Moore & Benbasat,

1996; Premkumar & Roberts, 1999; Thong, 1999).

Rogers’ (1995) framework comprised the following

factors: relative advantage, complexity,

compatibility, observability, and trialability. Relative

advantage is the degree to which using technology is

perceived as being better than using its precursor of

practices. Complexity is the degree to which

technology is perceived as being easy to use.

Compatibility is the degree to which using

technology is perceived as being consistent with the

existing values, and past experiences of the potential

adopter. Trialability is the degree to which

technology may be experimented with on a limited

basis before adoption. Observability is the degree to

which the results of using technology are observable

to others. Rogers’ (1995) compatibility characteristic

is highly envisaged here as past studies (Austin,

1992; Austin, Trimm, & Sobczak, 1995) have

considered the problem relating to physicians

accepting information technology (IT) for clinical

purposes. Cost was outlined as an important factor

by other researchers (Bacon, 1992; Elliot, 1996;

Tornatzky & Klein, 1982). Cost means the degree to

which technology is perceived as cost effective. The

image factor was found important to the adoption of

technologies in the health literature (Little &

Carland, 1991). Image means enhancing one’s

image or status in one's social system. Even-though

Rogers (1995) highlighted the importance of the

image factor on IT adoption he suggested that it

could be studied from within the relative advantage

characteristic. However, Moore and Benbasat (1996)

stressed the image factor as an independent factor on

its own. As TM projects involve considerable

investments, top management support is viewed as

important to the adoption decision (Kwon & Zmud,

1987).

2.1 Determinants of TM Adoption

In review of more recent literature it was observed

that despite the rapid growth and high visibility of

TM projects in health care (Grigsby & Allen, 1997),

few patients were actually being seen through the

TM for medical purposes. In almost every TM

project, tele-consultation accounts for less than 25%

of the use of the system (Perednia & Allen, 1995).

Other research reported mid-level success for

telemedicine projects (Guedemann, 2003). In a large

study in the US, Edwards and Patel (2003) found

that the clinical uses of the telemedicine network did

not exceed 30%. The majority of the online time was

used for medical education and administration

(Edwards & Patel, 2003; Wayman, 1994; Perednia

& Allen, 1995; Hassol, 1996). Earlier success stories

of telemedicine in countries such as the US

demonstrated that telemedicine was feasible while

maintaining diagnostic accuracy, which challenged

the widely held belief that a patient and a provider

must be in close proximity for healthcare to take

place.

The important unresolved issues revolve around

how successful TM can be in providing quality

healthcare at an affordable cost and whether it is

possible to develop sustainable business model that

would maintain profitability over time. This depends

on (Perednia & Allen, 1995): (1) clinical

ICE-B 2006 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON E-BUSINESS

192

expectations, (2) matching technology to medical

needs, (3) economic factors like reimbursement, (4)

legal (e.g., restrictions of medical practices across

state lines (licensure) and issues of liabilities), and

social (e.g., changing physician behaviors and

traditional practices and workflow) issues

(Anderson, 1997), and (5) organizational factors.

Edwards and Patel (2003) attributed the success of

TM projects to defined clinical needs, organizational

support, physicians’ and patients’ acceptance,

exhibiting measurable cost and clinical benefits, and

moving toward sustainable operations. Interestingly,

Whitten et al. (2002) in a comprehensive study

concluded that there is no evidence that TM is a cost

effective mean of delivering healthcare.

In their review of the literature, Finch et al.

(2003) supported the above factors and found the

following hurdles which could increase the

resistance to telehealthcare in practice:

i. telehealthcare is somewhat unstable.

ii. there are some concerns relating to the

doctor-patient interaction.

iii. concerns about clinical risk and potential

litigation

iv. at an international level, some difficulties

relating to licensure and reimbursement were

reported.

v. the production of evidence about the safety

and effectiveness of telehealthcare

vi. despite the numerous trials of telehealthcare

in Britain and elsewhere, such services

typically fail to become part of routine

healthcare delivery.

3 METHODOLOGY

This research is exploratory in nature in the sense

that there is no prior research in UAE to guide this

research in achieving the above objectives. Case

studies are appropriate for the exploratory phase of

an investigation (Yin, 1994). Therefore, this research

will follow the qualitative paradigm by adopting

Yin’s (1994) hard case-study methodology.

Yin’s (1994) positivist approach is acceptable by

the interpretivist school as well. For example,

Walsham (1995) indicated that although Yin (1994)

adopted an implicit positivist stance in describing

case study research, his view that case studies are

the preferred research strategy to answer the above

type of questions would also be acceptable by the

interpretive school. Details of the different cases are

provided in the following section.

Interviews were sought from many experts

involved in telemedicine projects in the UAE. Those

experts were: educational, specialists/surgeons, IT

and administrators/managers (Table 1). Those

experts were requested (after explaining the research

objectives and content) to complete a qualitative

survey questionnaire. Site visits were implemented

to FHMS and Tawam to see TM installations and

meet respondents.

Table 1: Respondents’ distribution across the different

cases.

Case Number

of respondents

UAE University 3

Tawam Hospital 4

Mafraq Hospital 1

4 THE CASES

4.1 FMHS

FMHS in UAEU uses the video conferencing

technology to deliver classes to male and female

students separately as classes are unisex and mixed

classes are not allowed within UAEU. Faculty

member alternate between female and male classes,

usually synchronized to take place at the same time.

For example, if a faculty member existed in the male

class; female students attend the same session in an

adjacent classroom through the video conferencing

link across the two classes.

4.2 Tawam Hospital

Tawam Hospital2 TM project represents a

partnership between UAE Ministry of Health and

Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota, USA).

Implementation started in September 2000 and first

case was sent in February 2001. The developers are

Mayo Clinics IT and Mayo Office of Middle East

Healthcare and Mayo subcontractor – Wellogic,

Boston, USA. Tawam TM technologies include: 512

Internet leased line; direct text captures entry;

digitized transparent images i.e X-rays, CT, MRI,

nuclear med, ultrasound, clear prints; digitized

reflective images, i.e. any paper print, document,

item needing scanning; CD drive to attach directly

still and motion films in DICOM format;

video/Audio conferencing; and fax.

The TM system is designed to handle

complicated patient consultations with the ability to

TELEMEDICINE ADOPTION AND DIFFUSION: THE CASE OF THE UNITED ARAB EMIRATES

193

transmit multimedia clinical information. Item that

can be transmitted include: Scanned paper medical

records; scanned X-ray films; digitized

echocardiography video; digitized cine-angiography;

and live videoconferencing.

There are four user groups that work closely

together to accomplish a TM consultation. These

groups include: UAE site requesting, UAE

telemedicine office coordinator; Mayo clinic

telemedicine office coordinator; Mayo clinic

consulting physician. Tawam adopted a standard

with Mayo clinic concerning reporting and receiving

patient consultations. Tawam reported that on

average, 4 cases were reviewed each month with

Mayo clinic.

Recently, Tawam established a large scale video

conferencing centre with the capability to have

simultaneous video sessions with several online

locations for meeting and educational purposes. The

centre will serve many clinical and administrative

staff as Tawam has signed with several international

medical centers and institutions to provide training

courses.

4.3 Al Mafraq Hospital

Similar to Tawam’s TM system where on November

1996, The Ministry of Health signed an agreement

with Mayo Clinic Foundation, Rochester,

Minnesota, USA to receive technical advice and

support in the design and construction of a TM

system to link three referral hospitals in Abu Dhabi,

Al Mafraq and Al Ain with Mayo Clinic for medical

e-consultation. As commented by one of the

respondents, “the TM system will be suitable for

store and forward as well as “real time”

communication link” and will be based on Mayo’s

experience of maintaining the integrity of patient

data, static images and full motion studies during the

process of digital acquisition, processing,

transmission and reconstruction. However, Mafraq

Hospital favored the “store and forward” option

more than the videoconferencing one as it does not

require that partners be present at the same time.

This is important specially if there is a time

difference between the two remote sites. Mafraq

implemented the solution using 512k internet link

through its Wide Area Network.

5 CROSS CASE ANALYSIS

Tawam and Mafraq adopted the same TM system

from Mayo clinic and hence, similar views were

unified into one depiction in this research in order

not to repeat reporting the same findings twice.

However, Tawam has adopted another large video

conferencing centre for education and meeting

purposes which could differentiate their responses

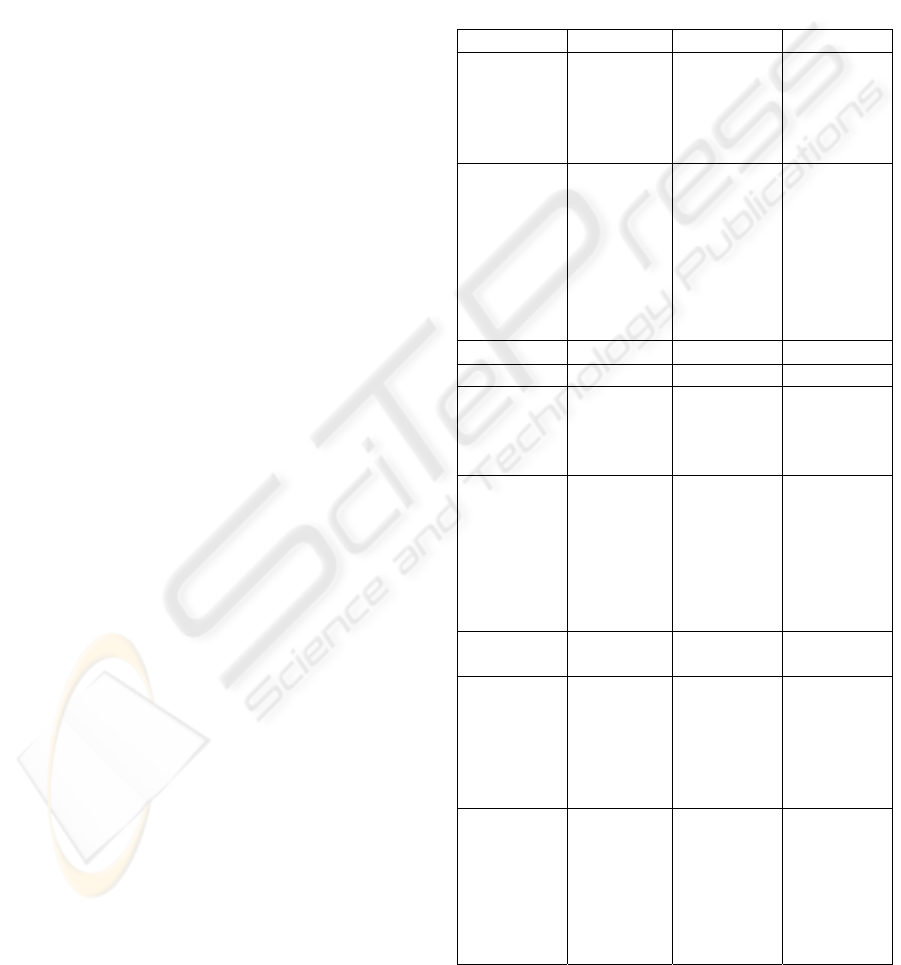

from Mafraq hospital. Table 2 summarizes the

research findings and analysis across the different

cases.

Table 2: Research findings and analysis across the

different cases.

Issue UAEU Tawam Mafraq

Advantages

Education Consultations

with Mayo

clinic

Education

Consultations

with Mayo

clinic

Complexity Not complex

Training and

onsite

support

should

remove any

complexities

Not complex

Not complex

Compatibility Compatible Compatible Compatible

Observability Important Important Important

Trialability Important

but difficult

to

implement

Important Important

Cost Not

important

An issue if

going to

bigger TM

projects

Not

important

Not

important

Image

Moderate

effect

Important Important

Top

Management

Support

Important

Simple

decision

process and

structure

Important -

role of the

Government

Important

UAEU

leading role

to encourage

others to

adopt TM

- -

ICE-B 2006 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON E-BUSINESS

194

Most notably, the relative advantages and the

compatibility factors attracted most of the

discussions amongst the different cases. Those are

explained next.

5.1 The Relative Advantages

All cases retained positive view about the potential

and the applications of TM in different departments

in their hospitals. The main issue raised by Tawam

is that some hospitals may not have the capabilities

and the needed resources to diagnose for specific

illnesses where TM could play a vital role here –

where they highlighted the following advantages:

i. Expanding the reach of the medical services

you can provide

ii. Reducing the costs associated with

unproductive travel

iii. Saving time away from clinical or educational

practice

iv. Sharing medical knowledge throughout

dispersed groups

v. Maintaining professional certifications without

going off-site

vi. Increasing team interaction, and improving

work flow and quality

vii. Sharing images easily for quick consultations –

across desktops

However, due to the educational role of FMHS,

they envisioned using the TM system for educational

purposes only, commenting “thus, the main focus of

telemedicine in FMHS is centred more on educating

future physicians than on providing immediate

medical service to patients outside the teaching

hospitals”. The same respondent commented that

“we have the specialists and the technology; we just

don’t have the mandate. We can, however, provide

specialty education in the way of CME to physicians

at a distance. The other specialty service that we

could provide to the Health Authority (and

physicians at a distance) is assessment of basic

competency skills through online exams (similar to

the Canadian Medical Council exam and the US

Medical Licensing Exam).” In addition, another

respondent from FMHS indicated that TM could be

used to supervise junior doctors or nurses in a

remote place, virtual attendance at overseas

conferences, importing/inviting conferences from

overseas, employment interviews and examining

research theses. This respondent confirmed that

these practices using have been implemented since

1994.

By adopting TM the hospitals (cases) could

provide health consultations to areas that these

services are not available. Mafraq hospital indicated

that the TM technology enables an electronic patient

visit virtually to Mayo Clinic without the

inconvenience and cost of traveling overseas. TM

delivers telehealth care services to hospitals like

Mafraq and Tawam Hospitals in the UAE for

medical consultation, referral, and second opinion. It

captures medical information electronically,

compress and transmit high-end resolution images,

digital full motion videos like angioplasty

procedures, colonoscopy, electronic EEG, MRI, CT

Scan, X-ray films, laboratory reports, and Digital

Clinical Still and Video Images.

Another respondent from Tawam confirmed that

TM could make specialty care more accessible to

underserved rural and urban populations in the UAE.

Video consultations from a rural clinic to a specialist

can alleviate prohibitive travel and associated costs

for patients. Videoconferencing also opens up new

possibilities for continuing education or training for

isolated or rural health practitioners, who may not be

able to leave a rural practice to take part in

professional meetings or educational opportunities.

Mafraq supported the same and raised other

advantages as well:

i. Provide more access to patients and families by

reducing the need for travel during severe

weather conditions.

ii. Reduce expense to patients and their families as

well as the UAE government at the hospital

level:

a. reduce travel distance & time away from

work/home for patients/families

b. provide a more efficient use of hospital

staff.

The other cases emphasized that they could

utilize TM in consultations, diagnostics, therapeutic,

in-surgery, transfer of patient related records, case

management, training & meetings (clinical/admin.).

One respondent from Tawam hospital envisioned

TM to be used in all clinics. Another respondent

from Tawam specified that TM could be used in

neurology, dermatology, gen/surgery, gastrology,

haematology, special Service, internal medicine,

ophthalmology, orthopaedic, urology, pediatrics and

gyn.

5.2 Compatibility

As for the compatibility aspect of the TM

technology, the cases did not view TM as

incompatible with them as such. For example, the

case of FMHS did report some issues concerning old

staff accepting the TM technology and

TELEMEDICINE ADOPTION AND DIFFUSION: THE CASE OF THE UNITED ARAB EMIRATES

195

administrative staffs were more comfortable using

the TM technology than doctors. However, such

incompatibilities could be reduced by providing

minimal training in order to build up experience

professional responsibility amongst faculty

members. With time, all clinical and administrative

staff would be encouraged to use TM.

The case of FMHS further commented that

change as a result of introducing new technology is

always difficult for some people. This is particularly

important in the case of people who feel they are

already stretched out with duties and tasks (like most

doctors). The case pointed that change could be

accelerated if there is clear and significant advantage

of using TM to doctors commenting, “they will be

motivated to change.” For example, medical faculty

staff had to learn how to lecture in simultaneous

video classrooms and had no trouble in dealing with

the TM technology. The majority of those faculty

members were quite proficient at using the

technology and adapting their teaching style to the

new environment – although the case of FMHS

admitted that faculty members had no choice but to

use the TM technology in running the simulcast

video classrooms commenting, “so that made the

need for adoption strongly convincing!.” FMHS

noted that more recent graduates were quite

comfortable with technology commenting “I believe

they will be the models for the use of technology in

medicine.”

Tawam strongly believed that by giving the TM

technology the chance to operate inside the hospital,

the staff will get used to it. Although Tawam

admitted that TM should be used more frequently by

doctors and administrators. The same respondent

indicated that TM could fit in easily amongst the

different technologies inside the hospital, i.e.,

integrate with Hospital Information System (HIS).

Other specific incompatibilities were reported as

well. From example, Tawam indicated that the still

video conferencing feature was not active due to

time difference between UAE and the US. Tawam

hospital reported that it was looking into signing

agreements with other known medical centers that

do not have significant time differences with them.

Also, they raised security concerns in sending

patient information over non-secure channels as one

of the impediments.

As for the compatibility of the TM with patients,

the cases pointed that this issue could be one of the

most difficult hurdles to overcome with respect to

the accuracy of diagnosis commenting “when 70%

of diagnoses are made from the patient interview, it

seems critical to be able to elicit this same amount of

information from patients using the TM

technology.” The case perceived that such expected

incompatibility could be reduced if there is a support

person in the room with the patient, such as a nurse,

this might help the patient to become more

comfortable. Tawam confirmed the same by

commenting “if it was necessary to have TM in the

remote location then yes.”

Another interesting issue reported here is that

patients favored traveling overseas over using the

Mayo clinic remote consultation service.

6 DISCUSSION

6.1 The Significance of the Research

Model

It was clear that the decision to adopt TM was

motivated by the relative advantage specifically, its

compatibility, lack of complexity, observability,

trialability, image enhancement to the cases, top

management support and the role of the government

in playing a leading role in the country for other

hospitals to follow. The cases have reported many

advantages as a result of adopting the TM

technology as detailed above. Although cost was

viewed as unimportant to the adoption decision of a

medical tool but it would play a role if the cases

opted to expand their TM initiatives beyond the

current simple TM technology in

collaboration/cooperation with Mayo clinic in the

US.

The different factors in the research model have

helped is shedding interesting light on the adoption

and usage of TM in the different cases. Most of the

factors appeared as positively motivating the

adoption decision of TM (Table 2). The implications

arising from this positivism are twofold. Initially, it

could be argued here that such positive views

represent a good foundation for the large scale

adoption of TM in the UAE and indeed, such simple

and imported “know-how” and successful initiatives

could facilitate the adoption of more complex TM

initiatives at the national level in the UAE.

However, this could only be judged upon initiating

such projects within the UAE first. Secondly, such

positivism was expected given the limited scope of

the adopted TM technology in the hospital-cases.

The lack of more comprehensive and interactive TM

initiatives in the UAE (networks of TM projects,

involved specialist in TM consultations in rural

settings, collaborative/cooperative TM initiatives

ICE-B 2006 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON E-BUSINESS

196

across hospitals and universities, etc.) could have

contributed to such response by the case. This

conjuncture could be supported or refuted upon

implementing such advanced TM initiatives in the

UAE. This is yet to be seen.

However, such finding does not undermine the

importance of the depicted framework as it helped in

gauging the respondents concerning different

important issues surrounding the adoption and

diffusion of the TM technology in their

organizations. Thus, it is important to keep

monitoring the progress of TM in the UAE

alongside the research factors and whether any

serious national initiative is being activated in

response to the above suggestions. This raises the

importance of conducting longitudinal research in

order to monitor and report such progress.

6.2 The Compatibility of TM

The compatibility factor attracted a lot of the

discussion in this research and indeed, policymakers

need to introduce training programs to address the

emergence of such possible incompatibilities

between people working in the health sector and

technologies in general and TM technologies more

specifically. Part of the compatibility factor, security

was raised as one of the impediments to the adoption

decision of TM and hence, introducing more secure

measures to protect data and people across the video

link could warrant against any breaches or hacking

activities.

Given the time difference between the UAE and

the US, the Mafraq and Tawam hospitals favored the

“store and forward” option more than the

videoconferencing one. Also it was convenient to

both hospitals as this solution does not require that

partners be present at the same time. However, this

limiting aspect needs to be resolved in order to

maximize the utilization of the TM technology to the

benefit of the hospitals in the UAE. The cases

suggested some solutions where for example,

Tawam hospital reported that it was looking into

signing agreements with other known medical

centers that do not have such significant time

differences with them. However, the suggested

national initiative could address such perspective

more effectively.

6.3 Research Implications and

Suggestions

The research findings lead to a conclusion that TM,

as a medical tool, is being adopted minimally in the

UAE context. Its use for educational and

administrative purposes is well noted across the

different cases. Indeed, this is one of the important

tools of TM but due to its strategic importance in the

healthcare area and to the fact that the UAE have

several rural areas and communities, it was expected

that the potential use of TM in serving these

communities was more extensive.

Accordingly, the implications here are twofold.

Initially, the use of this TM system seemed ideal in

this context (consultation and providing second

opinion). On the other hand, the second implication

points to the importance of exploring the effective

use of the TM in different areas – more specifically:

i. In an internal and rural settings. Healthcare

providers in the UAE need to consider

establishing TM initiatives that could

capitalize on existing medical specialties

and services within the country and devise

ways to integrate TM into these services.

This tight coupling between the TM

technology and medical practices is the

only way for TM to succeed in the UAE.

Providing TM services at the outset or in

parallel to existing medical services will

waive its importance as an efficient

technique or as a replacement to existing

inefficient/old medical practices or

services.

ii. In a regional setting. The potential

advantages of such effective medical and

social TM networks could have a profound

impact on the health and the wellbeing of

people within the UAE. This is of great

importance to the UAE’s context given the

extant geographical dispersion of the

different Emirates in the Federation, cities

and rural areas/towns.

TM could play a vital role in bridging many

gaps:

i. Shortage in specialty staff in rural areas.

ii. Shortage in specialty staff in main centers

(where Mayo clinic link is well justified here).

iii. Moving patient from rural areas to specialists

in main hospitals.

iv. Commuting specialist to rural health centers.

Encouraging linkages

(collaboration/cooperation) with other health centers

within the UAE to share resources, expertise and

knowledge. This could lead to the establishment of

specialty centers in certain health fields.

Running such TM networks could yield

monumental economies of scope/scale in the

medium to long term projections and could prove to

TELEMEDICINE ADOPTION AND DIFFUSION: THE CASE OF THE UNITED ARAB EMIRATES

197

be an efficient and an effective medical tool in the

UAE. The current TM systems in the UAE

represents an initial and a vital resource for such

networks as the quality of consultations provided by

such specialty centers like Mayo clinic represent a

climax in the area of healthcare in the world. At the

regional level, such TM networks could establish the

UAE as a leading healthcare destination. The UAE

is well qualified to occupy this position given the

witnessed economical, technological and educational

growth and the stable political and legal

environment. The culture and the social environment

in the UAE is characterized of being as open to other

cultures. However, learning from the experience of

other medical destinations in the region (i.e., Jordan,

Kuwait) is very important. Hurdles concerning the

TM technology such as obtaining approvals and

certifications of the TM equipment (i.e., from the

FDA), reimbursement, litigations, and licensure are

big concerns in the US but not to the UAE context.

These issues provide further drive to the adoption of

TM in the UAE.

The amount of resources provided by the

government to the adoption of latest techniques and

tools in healthcare are tremendous and indeed, TM

could be considered as one of these strategic

projects. Indeed, this alone could remove many of

the hurdles surrounding justifying the financial

efficacy of the TM in healthcare in the UAE. Such

hurdles at the beginning of any TM projects could

kill the project at its infancy.

What is yet to be seen is to push the current TM

initiatives into the more interactive ones (TM

networks). Of course, providing a strategy for the

effective use of such networks is very important as

well. Looking for leaders and product champions in

each hospital is very important. This fact was also

supported in this research. Given the technical and

social complexity of the TM technology, leaders and

product champions could play a vital role in

empowering and facilitating the adoption and the

usage of TM in their organizations in the UAE.

It could be argued/agreed here that the UAE

government is engaged in executing more urgent

projects (infrastructural) but that should not

undermine the fact that TM could be considered as

one of such priority/strategic tools. This is yet to be

seen as well.

7 CONCLUSION

This research has addressed many of the issues

surrounding the adoption and usage of TM in the

UAE from a theoretical and a professional stance

and pointed to several implications and suggestions.

Such findings are of great importance to

professional, policymakers and researchers

interested in the research findings in general or in

the UAE context more specifically. The research

calls upon such stakeholders to initiate more

comprehensive and interactive TM projects in the

UAE and to consider the TM technology as one of

the strategic building blocks of the national health

strategy in the UAE. Thus, elevating beyond the

current simple use of the TM technology and hence,

emancipating into more daring TM initiatives could

benefit the health sector in the UAE. This may not

necessary take the form of “big-bang” project and

indeed, such national initiative could be achieved in

phases. The research findings set broad guidelines

and suggestions for such stakeholders and indeed

more consequent research studies could monitor the

progress and the development of the TM technology

and the research model in the UAE.

REFERENCES

Anderson, J. (1997). Clearing the Way for Physicians: Use

Of Clinical Information Systems. Communication of

the ACM, 40(8), 83-90

Austin, C. (1992) Information Systems for Health Services

Administration. Michigan: AUPHA Press/Health

Administration Press.

Austin, C., Trimm, J., & Sobczak. P. (1995). Information

Systems and Strategic Management. Healthcare

Management Review, 20(3), 26-33.

Bacon, C. (1992, September) The Use of Decision Criteria

in Selecting Information Systems/ Technology

Investments. MIS Quarterly, 369-386.

Charles, B. (2000). Telemedicine can lower costs and

improve access. Healthcare Financial Management

Association, 54(4), 66-69.

Edelstein, S. (1999). Careful telemedicine planning limits

costly liability exposure; Healthcare Financial

Management, 53(12), 63-69.

Edwards, M.& Patel, R. (2003). Telemedicine in the state

of Maine: A model for growth driven by rural needs.

Telemedicine Journal and eHealth, 9(1), 25-39.

Elliot, S. (1996). Adoption and Implementation of IT: An

Evaluation of the Applicability of Western Strategic

Models to Chinese Firms. In Kautz, K., & Pries-Heje,

J. (Eds.), Diffusion and Adoption of Information

Technology (15-31). London: Chapman & Hall.

Finch, T., May, C., Mair, F., Mort, M. & Gask, L. (2003).

Integrating service development with evaluation in

telehealthcare: An ethnographic study. BMJ (327), 22

November, 1205-1209.

Grigsby, B. & Allen, A. (1997). 4th annual telemedicine

program review. Telemedicine Today, 5(4), pp. 30-42.

ICE-B 2006 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON E-BUSINESS

198

Guedemann, M. (2003). Success in telemedicine: Some

empirical evidence. Telemedicine Journal and e-

Health, 9(1), 1-2.

Harris, K., Donaldson, J. & Campbell, J. (2001).

Introducing computer-based telemedicine in three

rural Missouri countries. Journal of End User

Computing, 13(4), 26-35.

Kwon, T., & Zmud, R. (1987). Unifying the fragmented

models of information systems implementation. In

Borland, R. & Hirschheim R. (Eds), Critical issues in

information system research (252-257). New York:

John Wiley.

Moore, G., & Benbasat, I. (1996). Integrating Diffusion of

Innovations and Theory of Reasoned Action Models to

Predict Utilisation of Information Technology by End-

Users. In Kautz, K., & Pries-Heje, J. (Eds.). Diffusion

and Adoption of Information Technology (132-146).

London: Chapman & Hall.

Lemberis, A. & Olsson, S. (2003). Intelligent biomedical

clothing for personal health and disease management:

State of the art and future vision. Telemedicine Journal

and e-Health (The Journal of the American

Telemedicine Association), 9(4), 379-386.

Little, D., & Carland, J. (Winter 1991). Bedside nursing

information system: A competitive advantage.

Business Forum Winter, 44-46

Noring, S. (2000). Telemedicine and Telehealth:

Principles, Policies, Performance, and Pitfalls.

American Journal of Public Health, 90(8), 1322.

Oakley, A., Kerr, P., Duffill, M., Rademaker, M., Fleisch,

P., Bradford, N. & Mills, C. (2000). Patient cost-

benefits of realtime teledermatology – a comparison of

data from Northern Ireland and New Zealand. Journal

of Telemedicine and Telecare, 2, 97-101.

Office of Technology Assessment U.S Congress (OTA)

(1995). Bringing Health Care On Line: The Role of

Information Technologies, OTA-ITC-624.

Washington, D.C: US Government Printing Office.

Perednia, D., & Allen, A. (1995). TMVC Technology and

Clinical Applications. The Journal of the American

Medical Association (JAMA), 273(6), Feb. 8, 483-

488.

Premkumar, G., & Roberts, M. (1999). Adoption of New

Information Technologies in Rural Small Businesses.

The International Journal of Management Science

(OMEGA), 27, 467-484.

Rogers, E. (1983). Diffusion of Innovation.. New York:

The Free Press.

Rogers, E. (1995). Diffusion of Innovation.. New York:

The Free Press.

Thong, J. (1999). An integrated model of information

systems adoption in small business. Journal of

management information systems, 15(4), pp. 187-214.

Tornatzky, L., & Klein, K. (1982). Innovation

Characteristics and Innovation Adoption

implementation: A Meta-Analysis of Findings. IEEE

Transactions on Engineering Management, 29(11), 28-

45.

Walsham, G. (1995) Interpretive case studies in IS

research: Nature and method. European journal of

Information Systems, 4, 74-81.

Wayman, G. (1994). The maturing of TMVC technology

Part I. Health Systems Review, 27(5), 57-62.

Whitten, P., Mair, F., Haycox, A., May, C., Williams, T.

& Hellmich, S. (2002). Systematic review of cost

effectiveness studies of telemedicine interventions,

BMJ (324), 15 June, 1434-1437.

Yin, R. (1994). Case Study Research Design and Methods.

California: Sage Publications.

1

(MOH) Retrieved on 15/12/2005 from the web:

http://www.moh.gov.ae/

2

(TAWAM) Retrieved on 17/12/2005 from the web:

http://www.tawam-hosp.gov.ae/

TELEMEDICINE ADOPTION AND DIFFUSION: THE CASE OF THE UNITED ARAB EMIRATES

199