DESIGN AND MAINTENANCE OF TRUSTWORTHY E-SERVICES:

INTRODUCING A TRUST MANAGEMENT CYCLE

Christer Rindeb

¨

ack, Rune Gustavsson

Blekinge Institute of Technology, School of Engineering

P.o Box 520, SE37235 Ronneby, Sweden

Keywords:

Trust, trustworthiness, trust management, e-services.

Abstract:

Designing trustworthy e-services is a challenge currently undertaken by many actors concerned with the de-

velopment of online applications. Many problems have been identified but a unified approach towards the

process of engineering trustworthy e-services doesn’t yet exist. This paper introduces a principled approach to

deal with trust solutions in e-services based on a concern-oriented approach where end users’ concerns serve

as the starting point for the process to engineer appropriate solutions to trust related issues for an e-service.

The trust management cycle is introduced and described in detail. We use an online application for reporting

gas prices as validation of the proposed cycle.

1 INTRODUCTION

The dynamic human assessment of trust has been

identified as a major concern for user acceptance and

hence for deployment of efficient and successful on-

line applications. Not only do we need to ensure trust,

we need to create an environment and online sup-

port between end-users and e-service providers and

other actors. This means to both engender, and pro-

vide means for a positive trusting experience. Many

applications available online presuppose a high level

of trust, and thus low levels of perceived concerns or

risk taking by the user in order for users to utilize

the provided service. Examples today include online-

banking where sensitive financial information is ex-

changed between the bank and the bank customer on

a public network (i.e. the Internet) or e-health appli-

cations where sensitive personal information might be

sent over the public Internet infrastructure. It is in-

teresting to note that use of online banking, when it

was introduced in a larger scale a decade ago, indeed

was regarded with scepticism by a substantial num-

ber of new users, but is today generally accepted as

a trusted service. This example illustrates that trust

in e-services is in fact dynamic in nature, depending

on, as we will discuss later, time and context depen-

dent variances in concerns and familiarity. In this

paper we will address a principled way towards de-

sign, implementation, and maintenance of trustwor-

thy e-services. To that end we will, in the next Sec-

tion 2 Background, introduce a structured approach of

addressing trust concerns of users and transforming

those concerns into engineering principles of trust-

worthy systems. In Section 3, we will introduce a

trust management model geared at maintaining trust-

worthiness. In section 4, Validation, we analyse ex-

periences gained from a field experiment where the

e-service provided is ”Cheapest gas in the neighbor-

hood!”

1

. In Section 5, Trust and trustworthiness, we

summarize the main aspects on those topics. There-

after, in section 6 Related work, we outline some

other contemporary approaches towards trust and e-

services. In section 7 Conclusions and future work

we present our findings and point at future work. The

final section is the Reference section.

2 BACKGROUND

With a multitude of novel and existing e-services on-

line questions and concerns regarding trust and credi-

bility are of major concerns by stakeholders. In the

”early” days of e-commerce concerns about online

payments was frequently discussed as a main barrier

for successful online businesses (Nissenbaum, 2000).

Today general concerns about online payments are

1

A Swedish web site: http://www.bensinpris.se

100

Rindebäck C. and Gustavsson R. (2006).

DESIGN AND MAINTENANCE OF TRUSTWORTHY E-SERVICES: INTRODUCING A TRUST MANAGEMENT CYCLE.

In Proceedings of WEBIST 2006 - Second International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies - Society, e-Business and

e-Government / e-Learning, pages 100-105

DOI: 10.5220/0001256001000105

Copyright

c

SciTePress

less prevalent and it is likely that issues related to this

has been more grounded in general payment struc-

tures in our society, that is users won’t generally have

the same doubts with respect to online payments due

to enforced and developed practices in the credit card

payment industry.

Privacy- and credibility concerns and qualities re-

lated to accuracy of information published on the In-

ternet are other factors often mentioned in trust stud-

ies and literature. We will likely discover new con-

cerns requiring attention in the future both in exist-

ing and new e-services. We claim in the paper ”Why

trust is Hard” (Rindeback and Gustavsson, 2005) that

trust in artifacts is in fact an assessment by a user if a

product or service is trustworthy. Building trustwor-

thy systems is furthermore an engineering task based

on a basis of observations about what is perceived to

be trusting qualities. To support that task we have

introduced a model that takes user related trust con-

cerns and translate those into a set of trust aspects

(e.g., my credit card number, or my identity can be

stolen). For a given trust aspect there are usually sev-

eral trust mechanisms that could be implemented to

carter for the aspects (e.g., encryption of data or ac-

cess control). Those mechanisms typically are invis-

ible or difficult to assess by a common user. To that

end, the service provider has to provide the service

or product with signs (brand names, test results, and

so on) to help the user to assess if the service meet

her concerns in a way that ensure that the product is

trustworthy. Trustworthiness, however, is a dynamic

and context dependent concept since the perception

of signs and the required mechanisms changes over

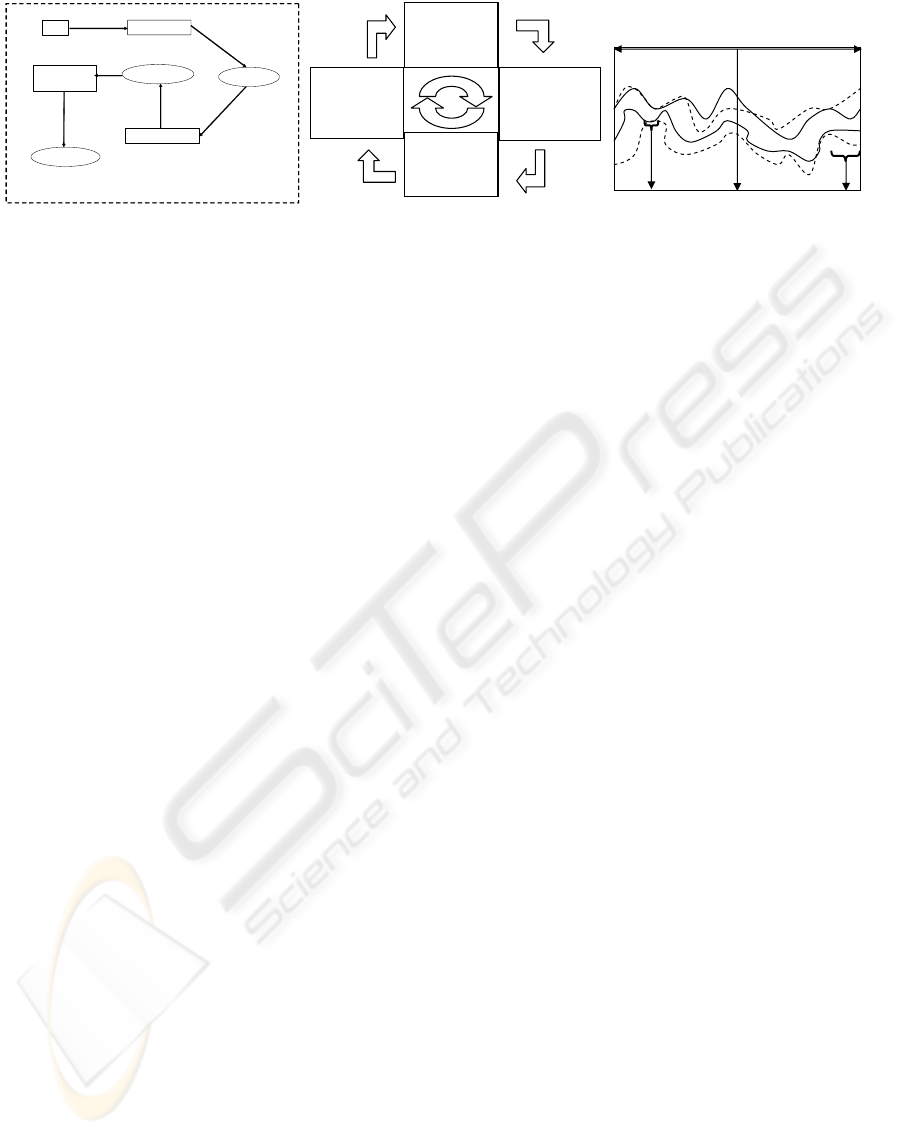

time. In order to maintain trustworthiness we propose

a trust management cycle (see fig. 1(b)). We will val-

idate our model by applying it on the ”Cheapest gas

in the neighborhood!” scenario example. As e-service

designers we can attempt to find a balanced solution

from a trust perspective that addresses the involved

actors’ different perspectives and trust concerns and

turn them into appropriate mechanisms. Ideally the

mechanisms should provide actors and end users with

signs for trust assessment purposes. The relationships

between these concepts are presented in fig.1(a)

3 THE TRUST MANAGEMENT

CYCLE

In this section we will take a closer look at how our

suggested approach can be broken down in a number

of steps. In fig. 1(b) we introduce the trust manage-

ment cycle, a model we propose to be used in order to

develop sustainable trustworthy e-services.

Step one: From Concerns to Aspects.The first step of

the trust management cycle is the initial component

of our model. The dynamic nature of both concerns

and perception of signs are forcing us to reflect and

constantly re-assess our efforts to comply with the e-

service users’ concerns. We need to ensure that the

identified trust issues are addressed. In fig. 1(c) we

illustrate the dynamics of trust concerns.

The gap between the upper and lower dotted curve

illustrates the current set of addressed trust concerns

of an e-service at a particular point in time. The filled

curves illustrate the set of actual trust concerns at a

point in time. With actual concerns we mean the set

of the actors’ and end-users’ concerns with respect to

a particular e-service at a particular time. We can il-

lustrate points before T (e.g. P) and points in time

after T (e.g. F). At time T in fig. 1(c) we can see

that there is a mismatch between the current actual

trust concerns and the addressed ones that may cause

an insufficient treatment of relevant concerns for trust

assessment purposes. There are other notable areas in

fig. 1(c) of interest; at the time interval P we see an il-

lustration of what we ideally want to achieve, namely

a match between the actual concerns that needs atten-

tion and the identified concerns. Under such circum-

stances we are addressing all relevant trust concerns

for the current context with respect to the e-service.

At the point F we are addressing too many concerns

that are outside the scoop of the actual concern do-

main at the time of investigation. This means that we

may address issues that aren’t actually perceived as

a concern from the perspective of the involved actors

and end-users. This can in turn lead to new concerns,

e.g. if privacy is addressed in a context where it isn’t

perceived as motivated it may trigger trust concerns.

Many concerns are similar and can be condensed into

more general classifications. For instance if we have

discovered many concerns related to the privacy of

personal information this can be derived into the as-

pect privacy. We summarize this first step as: ”What

trust concerns and aspects are we addressing?”.

Step two: from aspects to mechanisms. We can’t

deploy an aspect or trust concern directly into an

e-service application or it’s context. We need to

make a transition between the identified concerns

and aspects into deployable solutions. This process

include efforts to discover, engineer and develop

appropriate trust mechanisms. A trust mechanism

is a deployable solution that encompasses one or

more trust aspects. There is no one-to-one matching

between a trust aspect and a trust mechanism; instead

we may need multiple mechanisms to meet the

concerns addressed. Consider for instance the case

where the trust aspect privacy needs attention. First

we may need to deploy a privacy policy but this may

not be sufficient; we may also need to deploy and

join a certification program such as truste in order to

satisfy users’ concerns for trust cues. A mechanism

can also be used to satisfy multiple aspects. Such an

DESIGN AND MAINTENANCE OF TRUSTWORTHY E-SERVICES: INTRODUCING A TRUST MANAGEMENT

CYCLE

101

Trust Concerns

Trust aspects

Trust mechanisms

Trust signs

Perceived

trustworthiness

Input

Assessed trust

Context including actors, artifacts, e-services and work-

environments.

(a) Important trust concepts

1. What trust

concerns and

aspects are we

addressing?

2. What trust

mechanisms

should be

developed?

4. Do we need

to redesign or

implement new

mechanisms?

3. Do actors see

signs of trust-

worthiness?

5

(b) Trust management cycle

F

T

P

-+

Ti

me

(c) The dynamics of trust concerns

Figure 1: The trust management cycle and the dynamics of trust concerns illustrated.

example includes the mechanism ”data encryption”

which can be used to satisfy both security- and

privacy aspects. The transition from concerns and

aspects into the mechanism level is an important step

since it is here decided what we will implement into

the e-service with respect to trust. The mechanisms

can be implemented in more than just one way. A

privacy policy can, be a couple of rows long or

span over several web pages. Thus each mechanism

implementations may contribute uniquely to the

addressed concerns and aspects. We conclude this

step as ”What trust mechanisms should be designed

to present signs related to the trust concerns and

aspects?”

Step three: From mechanisms to signs. With deployed

and implemented trust mechanisms in place the ques-

tion is if our efforts are perceived by the actors and

end-users for the cause of trust assessment. We can

through our implemented solutions suggest that we

are trustworthy and taking care of the concerns the

end-users or actors may have. However trust and

what the observers see is subjective; we can’t enforce

trust or the wished behavior onto the e-service end-

users. We need to use measures to find out how and in

what way our efforts are perceived by actors and end-

users. Finding appropriate variables and measures is

challenging and can be done by various means. Our

trust management cycle in no way limits the approach

to determine how the efforts made to encompass the

identified trust concerns are made; however our ap-

proach is based on theories of signs, a concept used

by (Bacharach and Gambetta, 2001) in the context of

trust to illustrate the point that trust as such isn’t a

directly observable property, but rather we see signs

suggesting trustworthiness such as ”an honest look”

or affiliation. These signs are derived from the vari-

ous observable properties in place (an honest person

is a subjective observation based on e.g. the look of

that person). Likewise a person may comment that

somebody looks dishonest or unprofessional through

his or her way of dressing. The concept of signs in

our context is linked to the deployed mechanisms im-

plemented. Will there be signs pointing in the direc-

tion that the e-service provider seems to be ”honest”

(a trust aspect we strive to encompass through mech-

anisms) or are signs and thus sources to assess the

trustworthiness lacking? If we find a mapping be-

tween the identified concerns and the signs presented

this is a step into a better-engineered e-service from

the perspective of trust. The third step of the trust

management cycle can be concluded as: ”Do actors

and end-users see signs of trustworthiness that covers

the identified concerns?”

Step four: Assessment. In the previous stage we dis-

cussed the relationship between signs, mechanisms

and concerns. The re-assessment phase is the stage

where we closer reflect upon the e-service context and

the concerns we need to address in our solution. In

fig.1(c) we illustrate the dynamics of concerns and

we may need to reconsider from time to time which

concerns we need to address in our solution. For in-

stance at one point in time privacy may not be an

issue but because of changes in attitudes in society

and technical advancements these issues can become

more important at certain points in time. This en-

forces us to assess trust issues during the life span of

an e-service with arbitrary intervals. We also need to

reflect upon the validity of the deployed trust mecha-

nisms; are they still up to date or do they need fine-

tuning? Should a particular mechanism be removed?

If trust concerns are still in place we may need to in-

troduce new mechanisms or re-design present ones

for that partciular concern. In some cases e.g. aware-

ness of legal changes or if a particular encryption cho-

sen is hacked we may need to completely replace a

mechanism. This step can be summarized as: ”Do

we need to redesign or implement new mechanisms

or address new concerns?”.

Step Five: Gateway to the next cycle. The concerns

gathered and findings pointing us towards assump-

tions that the trust concerns aren’t properly addressed

WEBIST 2006 - SOCIETY, E-BUSINESS AND E-GOVERNMENT

102

trigger a new round in the model. Reasons for this

could be required changes of mechanisms or the intro-

duction of new ones for a particular set of concerns.

We also must consider if the concerns we are address-

ing are the right ones at this point in time.

4 VALIDATION OF OUR MODEL

Our ”Cheapest gas in the neighborhood!” service will

be used to illustrate how the trust management cy-

cle can be used to reason about trustworthy e-service

development. When the service was introduced the

prices of gas in Sweden were varying almost daily due

to the volatile global oil prices. Also there were local

price wars where the price levels between different

gas stations, could vary up to as much as 25% be-

tween closely located stations. Therefore people con-

sult the service from time to time to find information

about potential bargains on gas. If a price is lower in

one station some may consider reschedule their route

and in some cases even their destinations in order to

save some money. The e-service relies on price re-

ports submitted by it’s visitors who report prices by

filling out a form.

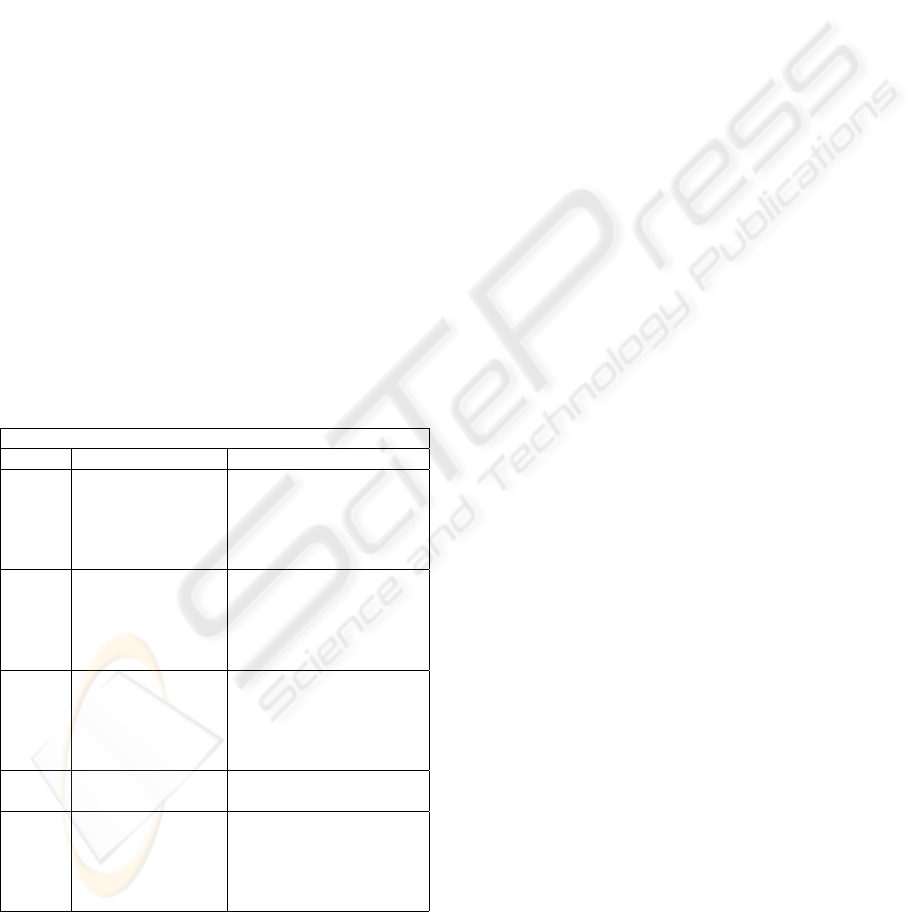

Table 1: Condensation of mechanisms and assessments

from our scenario.

Concern: Price and information accuracy

Cycle: Mechanism: Assessment of reactions:

1

Date policy Ok but still comments

published on site. where visitors want

Dates when the more information.

prices where

reported added.

1

Forum and e-mail A way to give feedback

for feedback was about site features.

deployed to

enable comm-

unication

2

Limits for false Invisible feature as long

pricing was as a user don’t attempt

introduced. to insert an

unreasonable

high or low price.

3

Registration Ok, but concerns raised

requirements regarding privacy.

4

Registration re- The function opened up

quirement became for anonymous

optional. Manual submissions.

approval of ano- Affected the will-

nymous reports. ingess to report prices

When the service was first deployed only one con-

cern had been identified on behalf of the end-users;

the information about the prices needed to be correct

and up to date. To avoid too old price quotes to be

published a date limit mechanism was deployed. It

was thought that this effort would mediate the correct

signs for information accuracy. This concern seemed

to be met during the initial stage of the e-service af-

ter deployment, but after a while it seemed like new

mechanisms was needed in order to assure that the

concern could be met. During the first assessment cy-

cle it turned out that users again were concerned about

the accuracy the published prices. E-mails and on-

line forum discussions revealed problems with false

reports. The initial idea was that users would be able

to spontaneously report price quotes without the need

to provide an identity. By filling out a form on a web

page the price report was published on the web site.

After misuse, which affected end-users credibility in

the e-service, mechanisms needed to be deployed in

order to sustain the trustworthiness. The problem was

addressed by forcing users to register in order to re-

port prices by stating name and email. However, it

turned out that some users where reluctant to sign up

due to privacy concerns. For this reason the registra-

tion solution became optional with manual reviews of

anonymous price quotes. Up until today this solution

has proved to function well. In table 1 we illustrate

findings from four cycles of the trust management cy-

cle.

5 TRUST AND

TRUSTWORTHINESS

Trust can be defined in many ways depending on

the context and circumstances, there simply is no

commonly agreed upon definition stating what trust

actually is. Trust is often seen as a mechanism used

to reduce complexity in situations of uncertainty

(Luhmann, 1988). If an online service is perceived

as to be trusted this may increase the likelihood

that the service is used by the truster although this

is no guarantee. Trust is by no means static, we

may have trust in e.g. a neighbor but due to some

event that ends with disappointments about their

behavior, or solely a suspicion about a behavior,

may cause the trust to decrease. The very opposite

may also be true since trust can grow depending on

signs suggesting somebody is to be trusted. We have

identified the following trust dimensions (Rindeback

and Gustavsson, 2005):

Trust in Professional Competence - When a decision

to delegate a task to another actor is taken this is often

based on a perception of that actor’s professional

competence. This refers to expectations about the

professional abilities (Barber, 1983) of e.g. a doctor

or banker and suggests further refinements of trust

expectations.

DESIGN AND MAINTENANCE OF TRUSTWORTHY E-SERVICES: INTRODUCING A TRUST MANAGEMENT

CYCLE

103

Trust in Ethical/moral Behavior - Trust isn’t only

related to professionalism in dealing with tasks as

such, it is also suggested to be linked to values

and less tangible nuances such as ethical and moral

premises. If a trusted professional acts in a manner

that is perceived as being against common ethical

and moral norms we can choose to distrust this

person in a given context despite his professional

skills. Examples include certain types of medical

experiments or other acts that can be regarded as

unethical or even criminal if detected. Trust in

moral or ethical behavior is, of course, very context

dependent. Moral and ethical trust is discussed both

in (Barber, 1983) and (Baier, 1986).

Trust in Action Fulfillment - In cooperation a specific

trust dimension surfaces in most contexts. That is,

can a subject trust that an object will indeed fulfill a

promise or obligation to do a specified action? When

ordering a product online concerns may for instance

be raised if it will be delivered or not.

Functionality - The functionality of an artifact is

an important and natural quality of trust, e.g., the

tools are expected to function as they should. An

implicit trust condition is that an artifact or tool is not

behaving in an unexpected or undesired way by its

design (Muir, 1994).

Reliability - The reliability of an artifact is another

important criteria of trust in classical artifacts.

The tools should be resistant to tear and wear in a

reasonable way and the e.g. a VCR should function

flawless for some years. Reliability thus means that

an artifact can be expected to function according

to the presented functionality and is working when

needed.

These dimensions of trust are related to one or more

objects, in which a truster place his or her trust

(Rindeback and Gustavsson, 2005):

Trust in social/natural order and confidence - Our so-

ciety rests on basic assumptions about what will and

will not happen in most situations. For instance we

have trust in the natural order, that the heaven won’t

fall down or that the natural laws will cease to be true.

There is also a general trust related to the social order

in most of our societies, that is that the governmen-

tal representatives will do the best for the citizens and

countries they represent and follow laws and norms

as well as follow established practices accordingly.

This mutual trust isn’t something that actors in gen-

eral reflect consciously about. The non-reflective trust

serves as a basic trust/confidence level for our daily

actions where in general there aren’t any alternatives

to the anticipated risks. The notion confidence (Luh-

mann, 1988) is sometimes used in situations where

actors in reality have no choice. It isn’t a viable op-

tion to stay in bed all day due to concerns about the

social or natural order.

Trust in communities - Humans are often part of a

larger community. In the society we have companies,

non-profit organizations, governmental institutions

and other groups of humans, which often act ac-

cording to policies, and interests of the community.

In many cases the trust may be attributed primarily

(or at least in part) in the behavior in a community

e.g. a hospital. On the other hand, a hospital may

be perceived as trustworthier than another due to

better reputation regarding the perceived treatment

and quality of their staff. Depending on the context,

trust by a subject may be placed on the object

being a community, an individual representing the

community, or both.

Trust in humans - In many situations we attribute

trust towards other humans, we may trust a particular

person about his capabilities or trust his intentions

about a particular action. When buying a used car

for instance we may trust a car salesman to a certain

degree or trust a neighbor being an honest person.

Trust between humans has been studied among others

by (Deutsch, 1973; Gambetta, 1988; Rempel et al.,

1985).

Trust in artifacts - Trust in human-made objects such

as cars or VCR:s are in some cases discussed in a

manner which implies that these objects can be seen

as objects in which trust is placed. For instance ’I

trust my car and VCR’. This means that our expecta-

tions regarding the objects with respect to reliability

are in some sense confused with or attributed for trust

in humans enabling the intended behavior.

The distinction between what or whom we trust is im-

portant when determining how to address trust issues

in a given context. E.g. if a patient don’t trust a doctor

this may have different causes which can be related to

the person as such (a human) and his or her profes-

sional competence, artifacts or maybe the reasons are

that the hospital as such isn’t to be trusted, the doctor

is just the representative towards the lack of trust is

attributed. When developing e-services we also must

consider the cause of particular trust concerns. Are

for instance the concerns technology-oriented or are

there other reasons for the identified trust concerns?

Trust and trustworthiness shouldn’t be confused.

An online vendor or a person can suggest that they

are trustworthy by their actions or through e.g. a web

site (Sisson, 2000). But it is up to the truster to assess

these suggestions.

WEBIST 2006 - SOCIETY, E-BUSINESS AND E-GOVERNMENT

104

6 RELATED WORK

Two strands of dealing with the problem of trust have

been identified. In some work and traditions there

is an implied idea that we can solve the problems

related to trust by encryption and security solutions

(Nissenbaum, 2000). Others suggest the need to cre-

ate an atmosphere of trust and understand issues re-

lated to different situations and actors. One approach

that deals with trust in risky environments such as

e-commerce is the model of trust in electronic com-

merce (MoTech) (Egger, 2003). It aims to explain

the factors that affect a person’s judgment of an e-

commerce site’s trustworthiness. MoTech contains of

a number of dimensions intended to reflect the stages

visitors goes through when exploring an e-commerce

website. The dimensions pre-interactional filter, in-

terface properties, informational content and relation-

ship management will be described below. Each of

these components addresses factors that have been ob-

served to affect consumers’ judgment of an on-line

vendor’s trustworthiness. Pre-interactional filters re-

fer to factors that can affect people’s perceptions be-

fore an e-commerce system has been accessed for the

first time. The factors presented are related to user

psychology and pre-purchase knowledge. The first

group refers to factors such as propensity to trust and

trust towards IT in general and the Internet. Pre-

purchase knowledge is related to Reputation of the

industry, company and Transference (off-line and on-

line). The second dimension of MoTech is concerned

with interface properties that affect the perception of

a website. Here the components are branding and us-

ability. Factors in the branding component are ap-

peal and professionalism. The usability component

factors are organization of content, navigation, rele-

vance and reliability. The next dimension, informa-

tional content contains components related to compe-

tence of the company and the products and services

offered and issues regarding security and privacy. The

fourth and last dimension reflects the facilitating ef-

fect of relevant and personalized vendor-buyer rela-

tionship. The components Pre-purchase Interactions

and Post-purchase interactions are related to factors

such as responsiveness, quality of help and fulfilment.

This model is interesting and divides the relationship

between the vendor and user into units that can be

analysed further.

7 CONCLUSIONS AND FURTHER

WORK

We introduced the trust management cycle, a princi-

pled approach to address the problem of trust in online

e-services in a structured manner which takes a start-

ing point in actual trust concerns expressed or identi-

fied in the user community. These concerns need to

be turned into deployable solutions by means of trust

mechanisms. We also presented validation of the cy-

cle by applying it on the ”cheapest gas in the neigh-

borhood!” scenario. We need to further validate the

model and investigate constituents of e-service con-

texts in order to find better ways to deal with trust

issues. We also see a need to understand the relation-

ship between specific signs and mechanisms in order

to better understand the characteristics of good trust

mechanisms. This will hopefully give us better tools

to deploy and design trustworthy e-services.

REFERENCES

Bacharach, M. and Gambetta, D. (2001). Trust as type de-

tection. In Castelfranchi, C. and Tan, Y.-H., editors,

Trust and deception in virtual societies. Kluwer Aca-

demic Publishers, North Holland.

Baier, A. (1986). Trust and antitrust. Ethics, 96(2):231–260.

Barber, B. (1983). The logic and limits of trust. Rutgers

University Press, New Brunswick, N.J.

Deutsch, M. (1973). The resolution of conflict; constructive

and destructive processes. Yale University Press, New

Haven,.

Egger, F. N. (2003). From Interactions to Transac-

tions: Designing the Trust Experience for Business-

to-Consumer Electronic Commerce. PhD thesis, Tech-

nische Universiteit Eindhoven.

Gambetta, D. (1988). Can we trust trust? In Gambetta,

D., editor, Trust : Making and Breaking Cooperative

Relations. B. Blackwell, New York.

Luhmann, N. (1988). Familiarity, confidence, trust: Prob-

lems and alternatives. In Gambetta, D., editor, Trust

: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations, pages

94–110. Basil Blackwell, New York, NY.

Muir, B. M. (1994). Trust in automation .1. theoretical is-

sues in the study of trust and human intervention in

automated systems. Ergonomics, 37(11):1905–1922.

Nissenbaum, H. F. (2000). Can trust be secured online? a

theoretical perspective. In A Free Information Ecology

in the Digital Environment, New York, NY.

Rempel, J., Holmes, J., and Zanna, M. (1985). Trust in

close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 49:95–112.

Rindeback, C. and Gustavsson, R. (2005). Why trust is hard

- challenges in e-mediated services. Trusting Agents

for Trusting Electronic Societies: Theory and Appli-

cations in Hci and E-Commerce. LNAI, 3577:180–

199.

Sisson, D. (2000). e-commerce: Trust & trustworthiness.

DESIGN AND MAINTENANCE OF TRUSTWORTHY E-SERVICES: INTRODUCING A TRUST MANAGEMENT

CYCLE

105