REDESIGNING INTRODUCTORY ECONOMICS

Techno-collaborative Learning

Maha Bali, Aziza El-Lozy and Herb Thompson

The American University in Cairo, Cairo, Egypt

Keywords: Educational technology, tertiary education, computer mediation, pedagogy.

Abstract: Does computer-mediation enhance student performance or student interest in the learning process? In this

paper we present the somewhat tentative results of an experiment carried out in teaching/learning

methodology and pedagogy. The goal of the experiment was to examine, compare and elicit results to

identify the differences, if any, in learning outcomes between two classes. One class was taught using

computer-mediated technologies in conjunction with “active” learning pedagogical principles; and the other

class was taught by the same instructor with identical course syllabi and textbook, but using a more

conventional approach of lectures and tests to achieve learning.

1 INTRODUCTION

As (Brahler et.al., 2000), argue, the combinatory

effects of increased workloads, larger classes,

changing learner needs and improved instructional

technologies all have resulted in an increased

demand for on-line teaching material. Consequently,

the aim of this project was to focus on creating a

learner-centred, formatively assessed, course that

used Web-enabled technology. Introduction to

Microeconomics, was chosen as the course to be

redesigned because it has many sections and because

it has a “broad institutional impact”. In order to

gather comparative data, another section of the same

course was simultaneously offered by the same

professor, utilising a more traditional “talking head”,

summatively assessed, approach.

We proceed in the following section with a

literature overview of computer-mediated learning.

This is followed by a description of the experiment

and the methodologies used. Given the data gathered

during the experiment, tentative results and

conclusions are delineated.

2 OVERVIEW OF

COMPUTER-MEDIATED

LEARNING

Does computer-mediation enhance student

performance or learning interests? In this paper we

examine the relationship between computer-

mediated technologies and student intellectual skills

and abilities (Salomon, Perkins and Globerson,

1991). It has been argued, and the premise is

accepted, that many students prefer the “talking

head” that enables them to sit and listen passively

while information pertinent to examinations is

organised for them. Other research shows that better

retention, deeper thinking and higher motivation is

initiated when students are actively involved in

talking, writing and doing things relevant to their

studies, both inside and out of class (Ahern and El-

Hindi 2000: 385-396). Student evaluations exist for

both types of educational practice (McKeachie 1997:

1219).

Implementing a change from the traditional

classroom to one of collaborative, computer-

mediated learning is not simple, either in

organisation and structure, or in the process of

carrying it out. The instructor is no longer the fount

of wisdom or the only purveyor of interpretation.

Even the hours of the class become manipulable by

157

Bali M., El-Lozy A. and Thompson H. (2006).

REDESIGNING INTRODUCTORY ECONOMICS - Techno-collaborative Learning.

In Proceedings of WEBIST 2006 - Second International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies - Society, e-Business and

e-Government / e-Learning, pages 157-163

DOI: 10.5220/0001238001570163

Copyright

c

SciTePress

students given the ability to log on to discussion

forums at any hour of the day and virtually, submit

assignments, read announcements gather

supplementary reading and ask or respond to

questions (Fuller, et.al. 2000). In any case, even with

the aforementioned technological advances, poor

pedagogical models emphasising the passive

absorption of “authoritative” information is being

passed onto students, thereby wasting the immense

potential of the Internet (Crook 1997; Kirkpatrick

and McLaughlan 2000). Clearly, the challenge is to

weave the technologies into the learning process so

that they become part of the process rather than an

adjunct to it.

Computer mediated technologies have and will

continue to have major repercussions on the

organisation and process of teaching and learning.

For those of us encapsulated in this process,

pedagogical approaches have come under more

scrutiny. Giving the student the chance to participate

more actively, interactively and collaboratively with

both peer groups and instructors is not only possible

but more easily achieved (Bailey and Cotlar 1994:

184-193; Ellsworth 1994; Ragoondden and

Bordeleau 2000).

3 DESCRIPTION AND

METHODOLOGIES OF THE

EXPERIMENT

Two parallel sections of the course (“traditional” and

“innovative”), taught by the same professor,

covering the same textual material, was offered in

the same semester.

The traditional section involved lectures only

(although students were encouraged to ask

questions), using power-point slides in-class. The

course syllabus and discussion forum was placed

online utilising WebCT and a textbook was used for

the required reading. Assessment was based on two

hard-copy pop quizzes (10% each), a midterm exam

(20%), two short reading assignments with students

required to provide a summary analysis in the web-

based discussion forum (15% each) class

participation (20%) and a final exam (20%). In

addition, a “learning styles” questionnaire (discussed

below) was placed in WebCT online.

The innovative section involved very little

lecturing by the instructor, but was facilitated mainly

as student-centred, with open class participation and

interaction. The students took turns giving short

lectures on the textbook material using power-point

slides in class. All course material, other than the

same hard copy text used in the other class, was

provided online and online discussion was overtly

encouraged. Assessment in this section included 10

weekly online quizzes (1% each), class and

electronic online participation (20%), a group

collaborative project that was uploaded and assessed

on WebCT for all students to see (30%), a learning

journal that was shared with the rest of the class

upon completion (15%) and the same final exam

given to the other class (25%). Here too, a “learning

styles” questionnaire was placed in WebCT online.

Classes were primarily “open forums” with learning

activities, peer instruction, group assignments and

individual participation. All of the students in this

class had a personal computer which was used for

most of the class assignments and activities.

Students were encouraged to use the computer as the

search tool for questions and gathering of

information. “Instruction” in this class was primarily

one of coordination and facilitation with assistance

provided as required when computer searching, peer

instruction or collaborative assistance amongst the

students was insufficient.

The usefulness and reasoning behind the group

projects and learning journal is discussed further to

stress the pedagogy involved.

3.1 Collaborative Group Projects

Utilisation of the Internet to assist in collaborative

learning at a sophisticated level has been discussed

in the literature for at least a decade (Crook 1997;

Edwards and Clear 2001; Light, et.al. 1997;

McAteer, et.al. 1997; Sosabowski, et.al. 1998).

Team (collaborative) learning emphasises a high

level of active involvement and a great deal of self-

management by students. The challenges include

determination of effective team member role

behaviours and skill, dealing with ‘free riders’, and

evaluation of individual performance within the

group (Aiken 1991; Alie, R., Beam, H. and Carey,

T. 1998; Boyatiz 1994; Malinger 1998; Ramsey and

Couch 1994). It was emphasised from the beginning

that the students were going to have to resolve all

“management” problems themselves as the

instructor was not going to “referee” squabbles or

disagreements. Secondly, to handle the ‘free rider’

problem, one-third of the project grade was based on

peer evaluation of their colleagues in the group

(Cheng and Warren 2000). Grades were given by

each student to the others in the group anonymously,

and these marks were averaged by the instructor.

The caveat by McCuddy and Pirie that: “students

generally receive little guidance as to how to assess

peers but are simply told to provide an evaluation for

WEBIST 2006 - E-LEARNING

158

each team member”, was taken seriously and given

credence. It is recognised that “peer assessment is a

challenge to experienced individuals and can be a

daunting task for the uninitiated” [2004: 154].

Therefore, detailed guidance was given.

Group projects are problematic, to say the least.

Some students do not wish to study/work with others

as they feel that they are held back by the group, or

forced to coordinate their efforts with others who

may have very different study habits, initiative or

ideas as to what is a “successful project”. These

students will insist that group work is time

consuming with little benefit and in no way provides

an enhancement of their learning. Computer-

mediated communication may become a problem

when members of the group log on at very different

times or indeed, may not log on at all during times

considered crucial for others in the group (“Is

anyone going to respond to the point I made

yesterday about sharing responsibility for the write-

up…”). The point is that the technology is not living

up to its promise NOW! (Harasim 1993: 119-130;

Ragoondden and Bordeleau 2000) In fact, Repman

and Logan (1996) argue convincingly that the

benefits of group oriented pedagogy works primarily

at a social and affective level rather than enhancing

learning. One reason for this, also identified in the

literature, is that collaboration does not work well

within introductory courses, which attract a

variegated group of students both in terms of

backgrounds and interests. Rather collaboration

appears to be more strongly correlated to learning in

professional and graduate courses where

homogeneity of background and interest is more

closely aligned (Muffoletto 1997). However, in this

class, small groups appeared to work reasonably

well.

3.2 Learning Journals

What distinguished a learning journal in this course

is the necessity to relate the theory and models of the

classroom to lived experience. The intention is to

both learn from the process of doing it, i.e.,

reflecting on lived experience in terms of

information gained from the course, and to learn

from the results, i.e., the application of classroom

theory and models to actions, discussions, reading

material or experiences that are encountered outside

the classroom. The journal provides an intellectual

platform for reflection on what is being learned as

well as its usefulness. It counteracts “spoon-feeding”

which are the hallmark of lecture notes and

handouts. Instead, a personal approach to learning is

emphasised allowing the learner to incorporate the

material in their own terms of understanding.

The specific instruction provided to the student is

as follows: You will complete a journal/diary of

approximately 250 words per week, over a ten week

period (2500 words total. You will keep a record as

to what you have learned that is relevant to your

studies and life, questions that have been raised in

your mind, identification of issues that you never

thought about before. This is not to be a diary about

what we did in class. It is to be a reflective journal

relating the material covered in class to the rest of

your life's activities, such as conversations,

experiences, economic activities in which you were

specifically engaged, or articles in newspapers read

based on the material covered in class. How do the

theory and models learned in this course connect to

your lived experiences outside class.

4 AVAILABLE DATA TO ASSESS

IMPACT ON STUDENTS

4.1 Learning Styles Questionnaire

There may be as many different learning styles in a

classroom as there are people, which should directly

impact on the way teaching is organised. Research,

experimentation and results of work by Richard M.

Felder and Barbara A. Solomon in this area is made

available. They have developed a questionnaire to

delineate amongst four dichotomous pairs of

learning styles. The four pairs are: 1) Active and

Reflective Learners; 2) Sensory-based and Intuitive

Learners; Visual and Verbal Learners; and 4)

Sequential or Global Learners. Examination of their

efforts at URL http://www.ncsu.edu/felder-public/

is recommended. This exercise was included in the

project at hand. Of course there are numerous “ifs”

and “buts” in the results of their work, but the

questionnaire is a most practical and useful tool to

get a mental image of the groups being taught. The

results are more anecdotal, than analytical, but may

provide room for consideration.

Results from questionnaire: Students in the

Innovative section were all “active” learners, slightly

sensory rather than intuitive, primarily visual, and all

sequential learners.

Students in the Traditional section were half

active and half reflective; slightly more sensory than

the innovative section, similar in visual orientation

to the innovative section and were split fairly evenly

but slightly more global in approach.

REDESIGNING INTRODUCTORY ECONOMICS - Techno-collaborative Learning

159

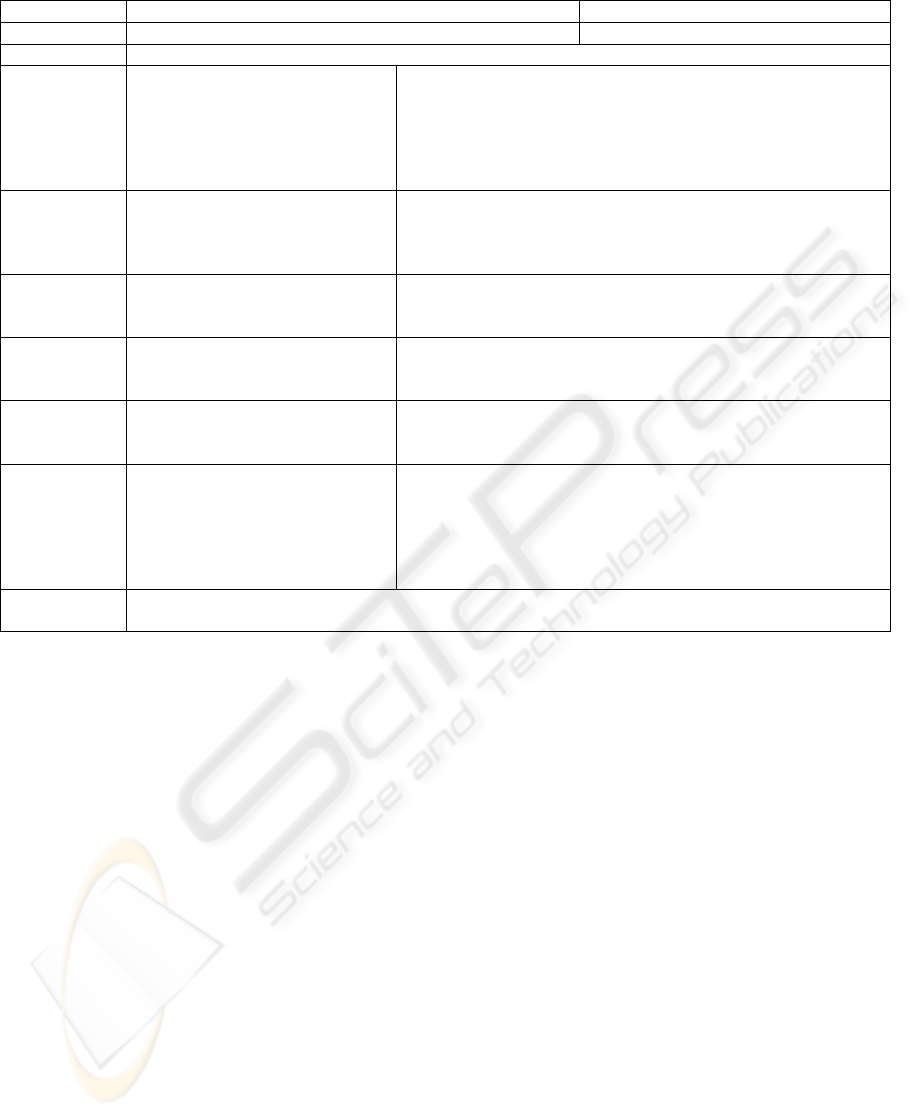

Table 1: Summary and Comparison of Teaching/Learning Approaches in each Section.

Characteristic Traditional Section Innovative Section

Population 20 (mostly 1

st

and 2

nd

year) 16 (mostly 1

st

and 2

nd

year)

Textbook N. Gregory Mankiw, Principles of Economics Chapters 1-17

Material

Online

Syllabus, topic notes, glossary,

ppt slides, learning styles

questionnaire, required and

additional reading, assignments,

calendar, bonus questions,

discussion forum.

Syllabus, topic notes, glossary, ppt. slides, learning styles

questionnaire, study guide, chapter links to relevant internet

material, links to classical scholars in economics, calendar, bonus

questions, discussion forum and quizzes. Student group projects

and learning journals were uploaded for viewing by the entire

class.

Lecture Lectures by instructor with .ppt

slides. Students were encouraged

to ask questions before and during

lectures.

Lectures by students using .ppt slides. Student centred, open

class participation and interaction encouraged (e.g., peer

instruction, group activities collaboration and sharing of

computer searches to solve problems or discuss issues)

Class

Environment

One computer, projector and

screen for professor

Class projector and screen for use by all. Each student supplied

with a personal computer. Software (Timbuctu) allowed any of

the computers to use projection screen.

Assignments 2 readings and summary analysis

uploaded on WebCT discussion

forum

Group project; Learning journal uploaded on WebCT

Quizzes 2 paper-based pop quizzes, with

normal assessment of correct

answers.

10 online quizzes – one per week. Following quiz, peers discuss

answers. Credit given simply for taking quiz

Direct

Assessment

2 pop quizzes – 20%

Class participation – 20%

Midterm – 20%

2 paper-based readings and

summary analysis – 20%

Final Exam – 20%

10 online quizzes – 10%

Class/Web participation – 20%

Class project – 30%

Learning Journal – 15%

Final Exam – 25%

Indirect

Assessment

Pre- and Post-course tests, Student evaluations, a Small Group Instructional Diagnosis, Learning

Styles questionnaire, WebCT tracking student activities

The instructor is seen as completely reflective

and much more intuitive than either of the sections,

but equally visual and verbal in approach, while only

slightly more global than sequential.

Description of Categories

ACTIVE – retain and understand best by doing,

applying or explaining.

REFLECTIVE – prefer to think about problems

quietly to begin with before acting.

SENSORY – prefer the facts and a “positivist”

approach; good at memorisation and lab work.

INTUITIVE – look for possibilities and

relationships and exceptions; comfortable with

abstraction and seeks innovation.

VISUAL – prefer pictures, diagrams, flow

charts, time lines, films and demonstrations

VERBAL – prefer written and/or spoken

explanation.

GLOBAL – prefer the “big” picture,

connections, interrelations and move almost

randomly to solution.

SEQUENTIAL – prefer linear step by step

approach to solution

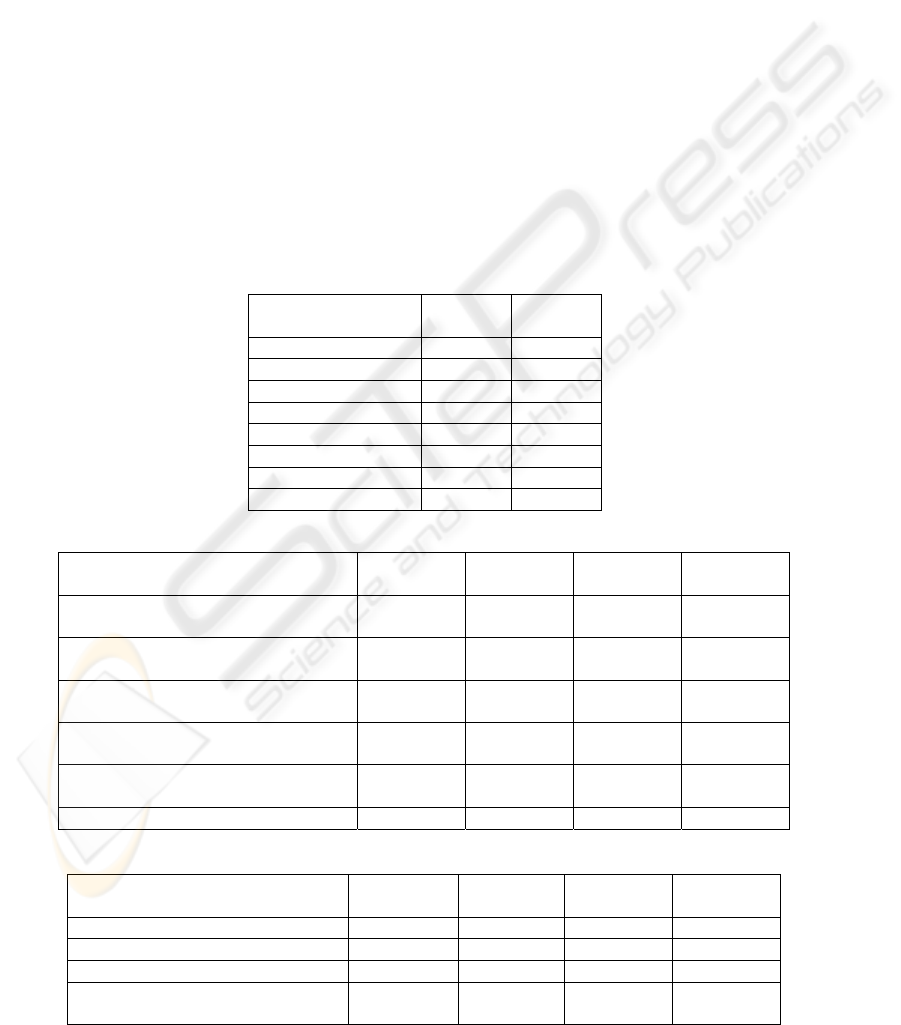

4.2 Pre- and Post-Course Test

Results

The pre-course test was taken from the Third edition

of William B Walstad and Ken Rebeck 2001 Test of

Economic Literacy, New York: National Council on

Economic Education which is used to measure

achievement of American high school students in

economics. A norming sample was provided

showing the aggregate statistics for a sample of

7,243 American students who had taken an

economics course. The numbers below are

representative of the number of correct answers out

of 40 questions. Both sections did better than the

norming sample, and had much lower standard

deviations. This suggests, that on the average, a

number of students in this course had previous

experience with Economics at the secondary level.

The post-course test was taken from the Third

edition of Phillip Saunders 1991 Test of

Understanding in College Economics, New York:

Joint Council on Economic Education which serves

as a measuring instrument in the teaching of

introductory economics at the college level for

WEBIST 2006 - E-LEARNING

160

comparative purposes. A norming sample was

provided showing the aggregate statistics for a

sample of 1,426 American students who had taken

the college course in economics. The numbers below

are representative of the number of correct answers

out of 33 questions. The Innovative section scored

similarly to the American sample, whereas the mean

of the Traditional section was lower than both, albeit

with a smaller standard deviation. See Table 2

below.

4.3 Comparative Assessment of

Final Exam and Final Grades

Summary: The results for the final exam and the

final grades were very similar for both sections. The

final exam results were (Innovative section – 75%,

Traditional section 74%) and the final grades were

(Innovative section had a mean grade of 83.8%

while the traditional section had a mean grade of

78.7%)

4.4 Comparisons of Student Course

Evaluation

In Table 3 the innovative section shows, overall, a

more positive attitude towards the course itself, but

the only significant difference is with reference to

the “reading materials”. This is most likely the result

of the variegated possibilities that the computer

offered the students in the classroom as a “library”

reference source and the facilitation provided to gain

access to up-to-date information relevant to the

material being studied in the text

. Table 4, with

reference to the instructor, shows similar results.

Although the innovative section ranks more

positively (with the exception of “explains concepts

clearly”) the differences are slight in every instance.

See Tables 3 and 4 below.

Table 2: Pre-course and Post-course test results.

Pre-test results Mean Standard

deviation

Traditional section 27.2 5.3

Innovative section 30.3 2.5

American sample 24.7 7.9

Post-test results

Traditional section 13.4 3.9

Innovative section 16.5 5.1

American sample 16.67 6.3

Table 3: Evaluation (Mean) of Course on a scale of 1-5 with 1 = Strongly Disagree; 5 = Strongly Agree.

Question Traditional

section

Innovative

section

Economics

overall

School of

Business

Reading materials are challenging and

stimulate my thinking

3.80 4.43 3.94 3.78

Tests and assignments reflect the

purpose and content of the course

4.30 4.29 4.18 4.03

Tests and assignments challenge me

to do more than memorize

4.40 4.57 3.97 3.86

The number and frequency of tests

and assignments are reasonable

4.10 4.43 4.17 4.00

The working load is appropriate for

the number of credits

4.30 4.43 4.08 3.91

Overall, this is a useful course 4.40 4.57 4.18 3.99

Table 4: Evaluation (Mean) of the Instructor on a scale of 1-5 with 1 = Strongly Disagree; 5 = Strongly Agree.

Question Traditional

section

Innovative

section

Economics

overall

School of

Business

Inspires student interest in course 4.29 4.33 4.08 3.94

Organised and prepared for class 4.43 4.56 4.45 4.23

Explains concepts clearly 4.00 3.94 4.19 4.01

Emphasises conceptual

understanding and critical thinking

4.29 4.41 4.15 3.99

REDESIGNING INTRODUCTORY ECONOMICS - Techno-collaborative Learning

161

4.5 Small Group Instructional

Diagnosis

In this exercise, the Director of the Center for

Learning and Teaching and the Instructional

technologist spent 30 minutes in each of the classes

interviewing the students as to their impressions of

the course half way through the semester. Below is a

summary of their responses to two questions.

What helps you learn in this course?

Traditional section

Power-point slides in conjunction with lectures but there

were a couple in the class who “hated” computers.

Understanding is expected more than memorization.

People asking questions: so that the point is covered again

and professor is prepared to go over questions again.

Innovative section

WebCT: permanent interaction; helps us to learn in an

innovative way (discussing amongst ourselves materials

that we may not comprehend).

No need to memorize – no mid-terms, so there is a need to

understand when writing in the learning journal. We have

to take much more responsibility for our own learning.

An interesting teaching style.

Discussions in class and feedback through the online

discussion is more important the sitting and listening to

lectures.

Students become the role players in the class, asking each

other questions and using the board and projector

ourselves to show our understanding to other students who

may not understand.

Always being up to date with what is going on in class and

outside class.

What improvements would you like and How would you

suggest that they be made?

Traditional section

Go slower

Spend more time covering class material relevant to

quizzes.

Provide more worksheets with practical problems.

Show relations between chapters.

More participation and discussion needed in class.

Don’t depend so much on WebCT

Innovative section

Provide more variety of choice for the group projects.

The discussion forum needs more structure and more input

from the professor.

Make all courses like this.

5 SUMMARY/CONCLUSIONS

5.1 Pre, Post, Final Exams

Given the intervening variables and relatively small

sample of students it does not seem appropriate to

discuss questions of “significant” difference.

However, practically, it can be noted that in all three

exams (Pre-test, Post-test and Final exam) the mean

and median results were higher for the innovative

section.

5.2 Course Evaluation

The numerical results of the course evaluation, and

qualitative observation by the instructional

technologist indicated better student disposition

towards the effect of technology on learning as well

as student motivation. General disposition towards

computer mediation was much stronger for the

“innovative” section students than for the traditional

section students (suggesting that it did enhance their

learning process, etc). The innovative course

consistently showed better results than either, the

traditional course, and other courses in Economics,

or all courses in the School of Business.

5.3 SGID

According to the SGID results the innovative section

students were more comfortable with the speed of

the course, the use of technology, and the material

covered. The traditional section students were

uncomfortable with the speed of instruction; felt

their questions were not sufficiently answered and

that the course was not sufficiently interactive.

Qualitatively, the students in the innovative section

seemed much more interested both in taking more

economics courses and/or taking economics as a

major; whereas the students in the traditional section

showed much less enthusiasm for the material

covered, or for economics as a discipline

.

5.4 CAVEAT

There is insufficient quantitative and qualitative data

to allow clear, undifferentiated judgements.

Furthermore, an excessive number of intervening

variables blurred both the accuracy and

interpretation of results, which, among other things,

is the analogue of Heisenberg’s “principle of

WEBIST 2006 - E-LEARNING

162

uncertainty”, i.e., the biases, attitudes and behaviour

of the facilitator.

No information was gathered with respect to

gender, major and minor degree interest, or student

backgrounds in economics in secondary school or

university.

To conclude qualitatively, on one level the

results indicate that the amount of work that goes

into creating an activity-based alternative to the

“talking head” and conventional testing approach

may be unnecessary. However, at another level there

was sufficient evidence to show that the learning

process (and economics) was enjoyed much more by

the students when engaged in an open, active,

collaborative manner. The depth of learning which

takes place remains to be determined in further

research.

REFERENCES

Ahern, T. and El-Hindi, A. E. (2000). Improving the

instructional congruency of a computer-mediated

small-group discussion: A case study in design and

delivery. Journal of Research on Computing in

Education, 32(3), 385-596.

Aiken, G. (1991). Self-directed learning in introductory

management. Journal of Management Education, 15,

295-312.

Alie, R., Beam, H. and Carey, T. (1998). The use of teams

in an undergraduate management program. Journal of

Management Education, 22, 707-719.

Bailey, E. and Cotlar, E. (1994). Teaching via the Internet.

Communication Education, 43, 184-193.

Boyatiz, R. (1994). Stimulating self-directed learning

through the managerial assessment and development

course. Journal of Management Education, 18, 304-

323.

Brahler, C.J., Peterson, N.S. and Johnson, E.C. (2000).

Developing on-line material for higher education: an

overview of current issues. Education Technology and

Society, 3(1), 42-54.

Cheng, W. and Warren, M. (2000). Making a Difference:

using peers to assess individual students’ contributions

to a group project. Teaching in Higher Education 5(2),

243-255.

Crook, C.K. (1997). Making hypertext lecture notes more

interactive: undergraduate reactions. Journal of

Computer-Assisted Learning, 13, 236-244.

Edwards, M.A. and Clear, F. (2001). Supporting the

Collaborative Learning of Practical Skills with

Computer-Mediated Communications Technology.

Educational Technology and Society, 4(1) [WWW

page]. URL

http://ifets.ieee.org/periodical/vol_1_2001/edwards.ht

ml

Ellsworth, J. (1994). Education on the Internet. Indiana:

Sams Publishing.

Fuller, Dorothy, Norby, Rena F., Pearce, Kristi and

Strand, Sharon (2000). Internet Teaching By Style:

Profiling the On-line Professor. Educational

Technology & Society, 3(2) [WWW page]. URL

http://ifets.ieee.org/periodical/vol_2_2000/pearce.html

Harasim, L. (1993). Collaborating in cyberspace: Using

computer conferences as a group learning

environment. Interactive Learning Environments, 3(2),

119-130.

Kirkpatrick, D. and McLaughlan, R. (2000). Flexible

lifelong learning in professional education. Education

Technology and Society, 3(1), 24-31.

Light, P., Colbourn, C. and Light, V. (1997). Computer

mediated tutorial support for conventional courses.

Journal of Computer-Assisted Learning, 13, 228-235.

Malinger, M. (1998). Maintaining control in the classroom

by giving up control. Journal of Management

Education 22, 43-56.

McCuddy, M.K. and Pirie, W.L (2004). Using teams in

the classroom: Meeting the challenge of evaluating

student’s work. In Ottewill, R., Borredon, L., Falque,

L., Macfarlane, B. and Wall, A. Educational

Innovation in Economics and Business: Pedagogy,

Technology and Innovation (Volume VIII, pp.147-

160). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

McAteer, E., Tolmie, A., Duffy, C. and Corbett, J. (1997).

Computer-mediated communication as a learning

resource. Journal of Computer-Assisted Learning, 13,

219-227.

McKeachie, W. (1997). Student ratings: the validity of

use. American Psychologist 52, November, 1218-

1225.

Muffoletto, R. (1997). Reflections on Designing and

Producing an Internet-Based Course. TechTrends,

42(2), 50-53.

Ragoondden, Karen and Bordeleau, Pierre (2000).

Collaborative Learning via the Internet. Educational

Technology & Society, 3(3) [WWW page]. URL

http://ifets.ieee.org/periodical/vol_3_2000/d11.html

Ramsey, V. and Couch, P. (1994). Beyond self-directed

learning: A partnership model of teaching learning.

Journal of Management Education, 18, 139-161.

Repman, J. & Logan, S. (1996). Interactions at a Distance:

Possible Barriers and Collaborative Solutions.

TechTrends, November/December, 35-38.

Salomon, G. Perkins, D. and Globerson, T. (1991).

Partners in Cognition: Extending Human Intelligence

with Intelligent Technologies. Educational Researcher

20(3), April, 2-9.

Sosabowski, M.H., Herson, K. and Lloyd, A.W. (1998).

Enhancing learning and teaching quality: integration

of networked learning technologies into undergraduate

modules. Active Learning, 8, 20-25.

REDESIGNING INTRODUCTORY ECONOMICS - Techno-collaborative Learning

163