PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT AND CONTROL IN

LOGISTICS SERVICE PROVIDING

Elfriede Krauth, Hans Moonen

Rotterdam School of Management, Department of Decision and Information Sciences

Erasmus University Rotterdam, Burg. Oudlaan

50, P.O.Box 1738, 3000 DR, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

Viara Popova, Martijn Schut

Department of Computer Science, Faculty of Sciences

Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, De Boelelaan 1081a, 1081 HV, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Keywords: Key Performance Indicators (KPI), Plann

ing Systems, Logistics Service Providers, System Development

Abstract: Output of a planning process is a set of assigned individual tasks to resources at a certain point in time.

Initially a manual job, however, in the past decades information systems have largely overtaken this role,

especially in industries such as (road-) logistics. This paper focuses on the performance parameters and

objectives that play a role in the planning process. In order to gain insight in the factors which play a role in

designing new software systems for Logistical Service Providers (LSPs). Therefore we study the area of

Key Performance Indicators (KPI). Typically, KPIs are used in a post-ante context: to evaluate a company’s

past performance. We reason that KPIs should be utilized in the planning phase as well; thus ex-ante.

The paper describes the extended literature survey that we performed, and introduces a novel framework

that captures the dynamics of competing KPIs, by positioning them in the practical context of an LSP. This

framework could be valuable input in the design of a future generation of information systems, capable of

incorporating the business dynamics of today’s LSPs.

1 INTRODUCTION

Planning is the process of assigning individual tasks

to resources at a certain point in time. Originally,

planning was a manual task, performed by a human

planner. Over the last decades information systems

have increasingly taken over this role in industries

such as road-logistics; in practice however the

human planner has still a considerable role. In order

to make the transition from planning input to

planning output, a planning system – manual or

computerized – must employ the proper objectives

to derive to an optimal planning. To gain insight in

this area, we consider the Key Performance

Indicators (KPI) literature. KPIs are typically used in

a post-ante context: to evaluate the past performance

of a company. We reason that KPIs could be utilized

in the planning phase as well; ex-ante.

The research question we pursue with this paper

is: Whi

ch are the performance indicators that have

an impact on operational performance of logistics

service providers? We briefly describe the Logistics

Service Providers (LSP) industry and shortly

introduce the KPI field (section 2). Then, we

undertake a literature review in the areas of supply

chain management and LSPs (section 3). Building

upon, we compose a framework for logistical KPIs,

considering a multi-dimensional and multiple

stakeholder perspective (section 4). Section 5 covers

validation. Future research directions and

conclusions are discussed in section 6.

2 LOGISTICS SERVICE

PROVIDERS AND KPI’S

The increasing focus on core competencies opened

up many business opportunities for Logistics Service

Providers (LSPs) (Christopher, 1998). LSPs, often

239

Krauth E., Moonen H., Popova V. and Schut M. (2005).

PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT AND CONTROL IN LOGISTICS SERVICE PROVIDING.

In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, pages 239-247

DOI: 10.5220/0002536102390247

Copyright

c

SciTePress

also referred to as Third Party Logistics Service

Providers (3PLs), carry out the logistic activities for

one or more companies within the supply chain;

functioning as an intermediary (Lai et al., 2004). The

functions of 3PLs or LSPs can be divided in:

warehousing, transportation, customer service, and

inventory and logistics management (Sink et al.,

1996), (Vaidyanathan, 2005).

Logistics service providing is an industry under

great pressure. Margins are small, and therefore

LSPs continuously seek for opportunities to make

their business more profitable. That can be, for

example, by scaling up or expanding their activities

outside their home country (Lemoine et al. 2003).

Planning and control is crucial for the operations

of an LSP: both for the day-to-day operations as well

as the more long-term strategic objectives. A good

insight in performance information and therewith

steering mechanisms for planning is important.

Historically, companies concentrated on financial

indicators. Nowadays it is widely recognized that

non-financial and even non-numerical indicators can

give valuable information as well (Brewer et al,

2000, Ittner et al., 2003). Such indicators though are

more difficult to measure and compare.

Selecting the right indicators for measuring (and

steering!) however is rather complicated. A full set

of indicators could result in a huge amount of data

which would require a lot of efforts and high costs

both in acquiring and analyzing. Another difficulty

is that it is not uncommon that the selected

indicators turn out to be conflicting – improving one

may worsen another.

Performance indicators are to a large extent

domain specific. Our research focuses on the area of

third-party logistics. But even here no unique subset

of indicators can be selected. The choice is company

specific and depends on the goals, state and

orientation of the company. Therefore it is

worthwhile to first concentrate efforts on providing

aid in the selection process. The existing literature

on performance measurement in logistics provides a

large number of potentially useful indicators.

3 LITERATURE REVIEW

KPIs are used to evaluate the past performance of a

company: making it possible to compare

performance with previous periods of measurement,

or industry standards or even individual competitors.

Consequently, any logistical system should try to

optimize and steer its decisions to the metrics it later

shall be evaluated upon. A clear insight into the

factors that drive logistical operations provides us

with adequate planning objectives.

In this paper, we review the different theories

and empirical findings known in literature on KPIs

in (road-) logistics. We specifically include elements

such as the multi-dimensionality of companies

(several hierarchical planning levels as well as

relevant business functions per company), general

business performance versus individual order

performance, and the principles of supply chain

management (steering a chain of companies versus

solely steering one’s own company). Note that the

perception of performance is relative: cost efficiency

may be one of the important measures for an LSP,

still this might not be what the shippers and

consignees desire – they would instead prefer high

quality and low price (Lai et al., 2004).

In the literature we identified two major

perspectives. First, there is a clear split between

performance indicator related research that focuses

on internal operations of an individual firm, versus

literature that takes the supply chain perspective and

seeks to optimize inter-organizational performance.

For one exception we refer the reader to Gibson et

al. (2002), which compared how shippers and

carriers rank service. The second perspective relates

to the use of performance indicators; in general the

indicators are used either at the strategic level, for

performance evaluation, or at the highly operational

level, for planning and control. In the next sections

we review the different sources of literature.

3.1 Supply chain performance

LSPs are specialists in supply chain management,

and are generally well aligned with the type of

supply chain they serve. Fisher (1997) makes a split

between efficient and responsive supply chains.

Christopher et al. (2002) make a similar distinction

into lean and agile. Weber (2002) is using a

hierarchical model to measure supply chain agility.

The Supply-Chain Operations Reference-model

(SCOR) offers a model with standards to describe

supply chains (SCOR, 2003). Measurements which

can be used to measure efficiency or leanness of

LSPs include fill rate of delivery plans, empty-to-

loaded backhaul mile index, equipment utilization

rates (hours), equipment utilization rates, vehicle

maintenance costs. Metrics to measure

responsiveness or agility include export shipment

processing time, delivery performance to customer

requested date, customs clearance time.

A strong partnership emphasizes direct, long-

term collaboration, encouraging mutual planning

and problem solving efforts.

Another important point is the use of information

systems (Sander, et al. 2002); as well as the type of

systems. Information systems support the integration

ICEIS 2005 - ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEMS

240

of inter-organizational processes (Hammer, 2001).

For an LSP information systems revolve around four

major players: the LSP’s customer, the customer’s

clients, the customer’s suppliers and alliances, and

the LSP provider itself (Vaidyanathan, 2005). Ross

(2002) shows that IT investment can have a positive

impact on market performance as a result of better

coordination in the value chain. However, putting

such a high level of collaboration into practice is not

easy. Both information quality and relationship

commitment play an important role (Moberg et al,

2002). As Kemppainen et al. (2003) suggest; it is

neither feasible nor profitable to have strong

collaboration with all supply chain partners. LSPs

should select key customers and focus on these

relationships. This then might result in different

types of inter-organisational systems: hierarchies

and/or markets (Graham et al., 1994), (Toni et al,

1994), (Lewis et al, 2000).

3.2 Performance management from

an internal company perspective

Whereas supply chain performance evaluation can

take many identities as has been shown above,

researchers agree on internal measurement, cost

calculation and performance evaluation methods.

Company-centred performance management focuses

on the measurement and evaluation of decision

making on company performance.

In the 1990s Van Donselaar et al. (1998)

performed a large-scale study in the transportation

and distribution sector in the Netherlands. They

focused on logistics performance from the

provider’s point of view – where they make a

division between distribution and transportation.

Their findings include the attractiveness of long trips

for long-distance transportation (which might be

influenced in the order-intake process). Furthermore

they show that a lower percentage of empty miles

(of total miles driven) leads to better results. Finally,

combining (international) shipments might be

beneficial, though it consumes more handling time.

UPS executive Peter Bromley (2001) lists the big

five KPIs important for UPS Logistics: on-time

receiving, on-time shipping and delivery, order

accuracy, inventory accuracy, returns cycle time.

Although low costs are important for UPS, the

perfect customer experience (through a perfect

service) seems to direct its business processes; for

other LSPs this may be different.

Similar findings were reported by Menon et al

(1998) who list the most important factors relevant

for customers in their selection of an LSP. Most

important are: speed and reliability, loss and damage

rate and freight rates (tariffs).

Delivery performance can be measured by on-

time delivery. This determines whether a perfect

delivery has taken place or not, it thus measures

customer service. Stewart (1995) identifies the

following as the measures of delivery performance:

delivery-to-request rate, delivery-to-commit date,

order fill lead-time and goods in transit. Quality and

the way the information is exchanged determine the

delivery performance to a large extent; possible

performance indicators are: number of faultless

invoices, flexibility of delivery systems to meet

particular customer needs. Measures of customer

service and satisfaction are flexibility, customer

query time, and post transaction measures of

customer service. See (Fowkes et al. 2004) for a

discussion on the reasons for delay and how

reliability and predictability is valued in industry.

Mentzer et al. (1991) study performance

evaluation in logistics. They identify a list of

performance measures in five sub-areas of logistics.

They differentiate between: labour measures

(loading, driving, general labour), cost measures,

equipment measures, energy and transit-time

measures.

Closely related to performance management, are

modern accounting methods, such as Activity Based

Costing (ABC) (Pirttila et al., 1995; Themido et al.,

2001). ABC differs from traditional cost accounting

by tracing costs to products according to the

activities performed on them. ABC has gained

acceptance within manufacturing; however, most

companies have not yet extended ABC to logistics

operations. In theory, the application of ABC within

an LSP would make it possible to trace costs to

specific orders, customers, or supply channels.

3.3 Planning levels

A company is usually divided into the levels

strategic, tactical and operational. Gunasekaran et al.

(2001) assigned metrics to the appropriate

management level. Van Donselaar et al. (1998)

distinguish between segments, which are marked by

the different services that are offered to customers.

The relevant costs on segment level were variable

costs (fuel, tyres, maintenance, etc.), direct costs

(depreciation, insurance, leasing, etc.) and driver

wages.

Lohman et al. (2004) perceive performance

measurement systems as process control systems. If

there is discrepancy between the actual and desired

value of a metric, knowledge about the behaviour of

the organization is used to modify the process. At

the tactical or strategic level the control loop is used

to evaluate the operational level and adjust its goals.

PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT AND CONTROL IN LOGISTICS SERVICE PROVIDING

241

3.4 Measuring the un-measurable

It is compelling to note that most literature focuses

on numerical factors such as: cost, time, faults, IT

utilization. Environmental factors, customer

perceptions, employee happiness, et cetera are

hardly covered in logistical performance indicator

literature. An exception is the balanced scorecard

which provides a formalized mechanism to achieve a

balance between non-financial and financial results

across short-term and long-term horizons and is

based on the notion that companies have to aim at a

true integration of marketing, production,

purchasing, sales and logistics (Brewer et al., 2000).

The balanced scorecard distinguishes four main

perspectives (Kaplan et al., 1992): customer,

internal, financial, innovation and learning. The

managers need to create their own version of the

balanced scorecard and concentrate on the most

critical measures.

Knemeyer, et al. (2003) study the perspective of

a customer. If the customer perceives that the LSP

focuses on the interaction between the companies

and is concerned with winning and keeping the

customer, the relationship can be strengthened.

Stank et al. (2003) examine how relational,

operational and cost performance relate to customer

satisfaction, loyalty and market share.

The internal business perspective translates the

customer perspective into what the company must

do in order to meet its customer’s expectations. But

the targets for success keep changing; and thus

innovation is needed. For LSPs innovations can

include additional activities, regions, transport

modes and communication systems e.g. RFID or

WebServices (Chapman et al., 2003, Lemoine et al.,

2003). Financial indicators measure if the

company’s strategy, implementation and execution

contribute to bottom-line improvement.

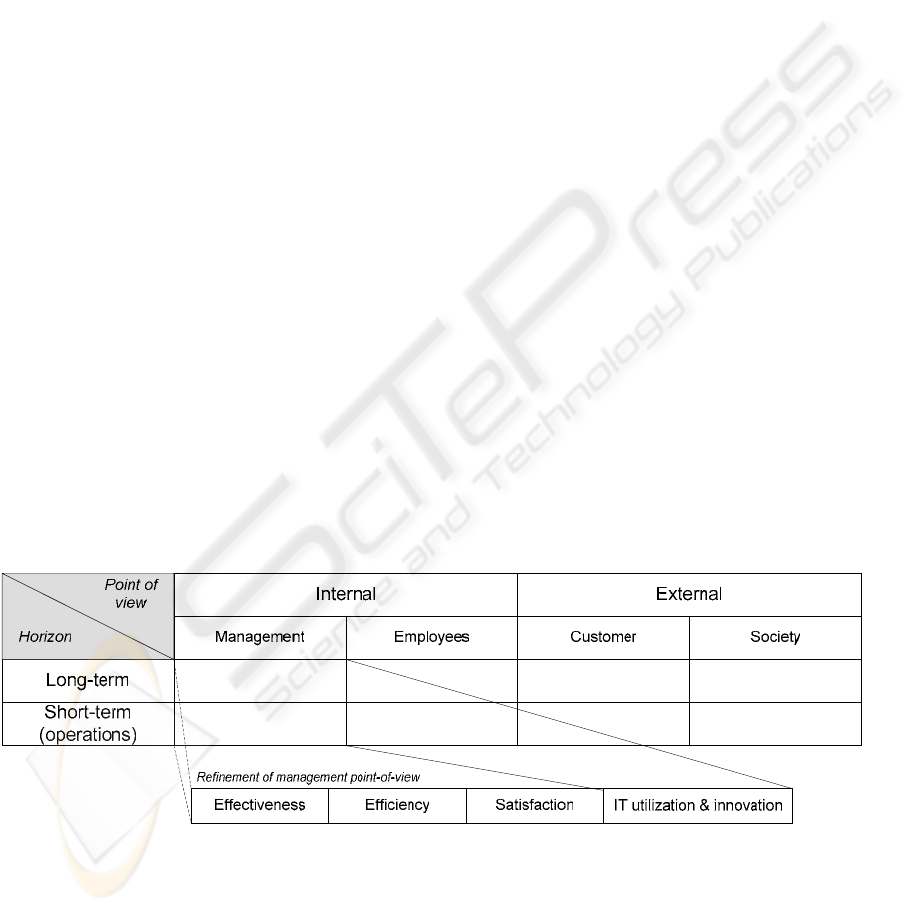

4 OUR FRAMEWORK

The literature overview presented in the previous

section supports the view that a new framework for

performance indicators can be beneficial in the area

of third party logistics. We consider different points

of view (both internal and external) on the

company’s performance. Figure 1 presents the

general scheme of our framework. On the horizontal

axis we separate the different viewpoints

corresponding to the parties involved. The internal

point of view is represented by the two parties

within the company – management and employees.

The external point of view shows the perspective of

the customer and the society.

The motivation for including four different

points of view comes from the fact that in many

cases they will be conflicting and, in order to

achieve a balance, the management should be aware

of the needs and desires of all parties involved.

Consider for example the prices for the logistics

services the company offers. Increasing the price

will bring more profit which is desirable for the

company. The customer, however, prefers low

prices. The society on the other hand is clearly not

so concerned with prices alone but more with the

economic climate as a whole, e.g. how to increase

the competition, fight monopolies, etc. Employees

are in general not so concerned with the prices but

with their work conditions. Another example would

be labour efficiency. Management is interested in

maximum utilization of labour which, without

applying restrictions, will lead to overexploitation.

This naturally comes in conflict with the point of

view of the employees. The society might be

concerned with cases of overexploitation on a large

scale that leads to drastic increases in accidents,

strikes disrupting traffic or health insurance issues.

The vertical axis in Figure 1 divides the

performance indicators in long-term and short-term.

This distinction has been previously used in other

research (e.g. Gunasekaran et al, 2001) and is

accepted as a meaningful division that the decision

makers find applicable. Short term indicators can

be measured for example within the period of a

month. The final choice of short term indicators

depends on organizational strategy and

measurements costs. For instance, an organization

aiming at maximizing its total number of driven

kilometers would want to report this on a daily basis.

Progress in information and communication

technology might lower costs for more granular

measurements. Long term performance indicators

are measured over longer periods of time.

The classification discussed so far is very

general. It incorporates all relevant points of view

but does not provide structure within these

viewpoints. Thus we extend it in this direction. An

extra extension has been added for the management

point of view, the KPI scheme has been further split

in four categories; see the lower part of Figure 1.

The reason for only enriching the management point

of view is that we expect it to accumulate a richer

collection of indicators where further refinement

will be necessary. We differentiate between the

following four categories:

Effectiveness – Effectiveness measures the

capability of producing an intended result. It thus

concerns the ‘outside’ of the organization – what

results does the organization achieve?

Efficiency – Efficiency is the measurement for

producing results taking into account used resources.

ICEIS 2005 - ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEMS

242

It thus refers to the ‘inside’ of the organization –

how does the organization achieve its results? We

may also say that efficiency measures the ratio

between input and output.

Satisfaction – Satisfaction represents the human

factor in our model. All organizational achievements

may be optimal regarding effectiveness and

efficiency, the people in the organization should still

be able to do their work to some degree of

satisfaction. In this way, it makes the performance

optimization problem of the organization more

constrained.

IT and innovation – An organization must also

be concerned with its future performance. As such,

innovation and IT utilization are indispensable

factors for measuring long term performance. An

organization that is working optimal now may not be

the best tomorrow if it does not take its own

circumstances into reconsideration constantly.

We applied this framework to our extensive

collection of performance indicators; for results see

Table 1.

5 FRAMEWORK EVALUATION

We present here preliminary validation results

although validation is at the time of writing not yet

completed. We conducted an expert interview to

cross-validate our model with feedback from

industry. We plan to conduct field studies with two

LSPs (i.e. with management and planners). After

finishing our evaluation, we intend to use the

framework and its indicators in the development of a

new agent-based software system for road-logistics

planning.

5.1 Expert interview

The interviewee prepared for the interview by

reading a draft version of this article, i.e. the

literature review, and the definition part of the

framework. The semi-structured interview lasted for

one-and-a-half hours. The interviewer started with a

short introduction. He explained in ten minutes what

the purpose was of this interview, what has been

done so far, and what future plans were.

Furthermore he made clear why especially this

interviewee was selected. Over the next seventy-five

minutes, the interviewee gave his vision on

performance measurement and performance

indicators. His thoughts were guided by twenty

years of logistical industry experience. At the end of

the interview, the interviewer used five minutes to

summarize the points discussed in the interview,

which were confirmed by the interviewee. The

results of the interview are presented below, in Table

2; it contains a summary of the most relevant aspects

discussed during the interview; before publication it

was checked with the interviewee.

Figure 1: High-level framework to cluster KPI’s relevant for LSPs

PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT AND CONTROL IN LOGISTICS SERVICE PROVIDING

243

Table 1: List of clustered performance indicators for LSPs

Internal perspective - Management point of view

Effectiveness

Revenue ↑

Profit margins ↑

Capacity utilization ↑

Km per day ↑

Labour productivity ↑

Price ↑

Turnover per km ↑

Number of deliveries ↑

Benefit per delivery ↑

Trips per period ↑

Perfect order fulfilment ↑

Total number of orders ↑

Number of customers ↑

Number of new customers ↑

Number of regular customers ↑

Number of profitable customers ↑

Continuous improvement, rate ↑

Product range ↑

Plan fulfilment ↑

Total loading capacity (for trucks) ↑

On-time delivery performance ↑

Long term plans availability / development ↑

Market share width ↑

Number of markets that have been penetrated ↑

Successful contacts – % of successful deals out of the initial offers ↑

Effectiveness of distribution planning schedule ↑

% of orders scheduled to customer request ↑

% of supplier contracts negotiated meeting target terms and

conditions for quality, delivery, flexibility and cost ↑

Competitive advantage ↑

Efficiency

Total distribution cost ↓

Labour utilization ↑

Overhead percentage ↓

Overtime hours ↓

% Absent employees ↓

Salaries and benefits ↓

Controllable expenses ↓

Non-controllable expenses ↓

Customer service costs ↓

Order management costs ↓

Inventories ↓

Number of trucks in use ↑

Total delivery costs ↓

Average fuel use per km ↓

Average delivery re-planning time ↓

Marketing costs ↓

Failure costs ↓

Prevention costs ↓

Appraisal/Inspection costs ↓

% of failed orders ↓

% of realized km out of planned km ↑

Performance measurements costs ↓

Human resource costs ↓

Variable asset costs ↓

Fixed asset costs ↓

Information system costs ↓

Overhead/management/administrative costs ↓

Quality of delivery documentation per truck/driver ↑

Effectiveness of delivery invoice methods ↑

% orders / lines received with correct shipping documents ↑

% product transferred without transaction errors ↑

Item/Product/Grade changeover time ↓

Order management costs ↓

Supply chain finance costs

↓

Total supply chain costs ↓

Total time in repair (for trucks) ↓

Ratio of realized orders vs. requested orders ↑

Average delivery planning time ↓

Satisfaction

Attrition of drivers ↓

Morale, motivation of personnel

↑

On-time delivery performance ↑

Number of customer complains ↓

Overall customer satisfaction ↑

% of orders scheduled to customer request ↑

Overall employees satisfaction ↑

Overall society satisfaction ↑

IT and innovation

Information system costs ↓

Up-to-date performance

information availability ↑

Utilization of IT equipment ↑

IT training costs ↓

Number of new products in the range ↑

% of information exchange through IT ↑

% of employees with IT training ↑

Availability of IT equipment ↑

% of information management assets used / production assets ↑

% of invoice receipts and payments generated via EDI ↑

Average time for new products development ↓

Average costs for new product development ↓

Internal perspective – Employee’s point of view

Km per trip ↓

Working conditions ↑

Weight to (un)load per labour hour ↓ Salaries and benefits ↑

External perspective – Customer’s point of view

Transportation price ↓

Insurance price ↓

Primary services price ↓

Goods safety ↑

Product variety ↑

Response time ↓

Transparency for a customer ↑

Possible types of communication ↑

Available types of goods insurance ↑ Order

size flexibility ↑

Timeliness of goods delivery↓

Services variety ↑

Order configuration flexibility ↑

Possibility to change order details ↑

Additional services price (priority transportation) ↓

Contact points (number of people to contact) ↓

External perspective – Society’s point of view:

Level of CO2 emission ↓

Society satisfaction ↑ Wasting

resources ↓

Recycling level ↓

Employees satisfaction ↑

Disaster risk ↓

Solid particles emission ↓

Taxes to the national treasury ↑

Participation in charitable actions ↑

Reputation of a company ↑

Road maintenance costs ↓

Number of available work places ↑

Competition level among similar companies ↑

Care for animals/children around ↑

Use of innovation technologies ↑

Development of innovation technologies ↑

Cooperation with other companies ↑

ICEIS 2005 - ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEMS

244

Table 2: Expert Interview

In traditional Operations Research (OR), operations are often rated and optimized upon a small set of parameters only –

sometimes only one single parameter. This results however in non-optimal system behaviour. Consider the example of

empty-kilometer minimization. This optimization often results in trucks standing still, waiting for a next order (preferably

with a starting point equal to the place of waiting). Trucks do not anticipate on the next order (in a more fruitful region).

Often waiting time does cost money as well – the driver needs to be paid and the truck could have been utilized for other

purposes. Reviewing single optimization parameters can hardly be seen separate from other indicators, as the following

indicates: Let us consider an LSP that has a truck driving around with only one small package – so, it uses only 5% of its

carriage capacity – utilizing a very inefficient route, with lots of detours. It is however not driving around empty – so from

an empty-miles perspective this truck operates very effective. Although we do realize that the truck could have carried more

cargo, and the route it took could have been more efficient. However, we do not know yet whether the customer is actually

paying for this trip – because if so, no LSP would mind to have a truck driving around via an inefficient route, with only

little cargo as long as the customer is paying a good price.

Not all indicators do have a direct translation in costs, or financial measurements, but do translate in, for example, extra

appreciation from the customer. An interesting example is Cehave – a Netherlands based organization active in the agri-

business. When delivering feed products to farmers, farmers prefer and value it to be the first farm on the delivery-

roundtrip, since with each extra visit (between Cehave’s plant, and the farm) the risk on animal diseases and infections

rises. The paradox however is that, although farmers prefer the service of being the first customer, they are not willing to

pay for this service.

Agility is more-and-more required for LSPs business operations. It is very important to have a flexible business

infrastructure, capable of quickly reacting and adapting to changes in operations: new orders, re-routing of a truck, or

handling changes in the environment (such as a traffic jam). Therefore quick react capabilities are of true importance;

measuring these however is a complex matter.

Planning systems targeted at such industries could well be build by using agent technology, and dynamic systems

(control) structures; utilizing measurement and reaction mechanisms to derive to smart decisions. [We] believe that smart

local decision making, making the right decisions at the right moment and right place are likely to result in well behaving

planning systems. Feedback plays an important role in such systems. Performance measurement should not only look at the

parameter as such, but also at the way those parameters change (and behave) over time – thus be aware of the first or second

derivative of the function as well.

The framework as presented in this paper is very interesting. It is finally an attempt to have a complete scheme, looking

beyond just financial indicators, and especially dedicated for the logistical industry. It measures more than solely costs, like

it also captures perceptions (of management, customers, employees at different levels, et cetera). A very useful division is

the split between the strategic, tactical, and operational time-domains. It might furthermore help in overcoming problems in

supply chains that want to assess chain wide performance. However, some adjustments and generalizations might be

needed.

Critical notes on the work include: a subdivision/refinement as was made for the classification of the management

point-of-view (see Table 2) should be made for all the categories as mentioned in the framework, thus including employees,

customer and society as well. Therewith the framework becomes three-dimensional. Be aware that optimal, does not mean

the same to all companies. Optimal for one company, can be far from optimal for another company.

Interesting aspect of the presented work is that it could serve as a tool that makes performance indicators, and therewith

system-control a discussable issue in an organization – which would be a real valuable tool to evaluate current systems, and

to design future systems. The true advantage of this approach is that it could be relatively easy translated into an agent-

based software system. With software agents monitoring and controlling single performance indicators, and steering upon

these.

6 CONCLUSIONS

The contribution of this paper is twofold. Firstly, we

present a literature survey on the concept of

performance indicators in logistics. Secondly, we

present a framework capturing the dynamics of

performance indicators for LSPs including an

extensive list of LSP performance indicators.

The literature survey identifies a number of

studies on performance measurement/evaluation for

logistics. However, these studies are mainly on a

particular area or case and are focused on external

and quantitative indicators. Our review has

considered the areas of supply chains, internal

company performance, planning and qualitative

indicators.

The framework that we present is a first step

towards our long term aim to use performance

indicators ex-ante rather than post-ante. The model

considers indicators along two main dimensions. On

PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT AND CONTROL IN LOGISTICS SERVICE PROVIDING

245

the one hand we look at the perspective: internal

(management, employees) and external (customer,

society); on the other hand we classify indicators as

short-term or long-term. We identify the cost of

measurement of an indicator as essential in choosing

whether an indicator is eligible for pre-ante

monitoring and analysis. We have validated our

framework with a domain expert, and have planned

multiple case-studies and interviews for validation

as future work.

Other directions for future work include

obtaining more insight in the relationships between

the indicators as well as the relationships between

indicators on different aggregation levels. The

knowledge gained will be applied in the DEAL

project – which aims at the development of an

agent-based software system for road-distribution

planning. In such a system we represent the involved

logistical parties as agents operating within a multi-

agent system. In order to give the agents the proper

decision objectives, insight in logistical KPIs is

needed. Finally, we are currently developing a

formal language for expressing the relationships

between the indicators and reasoning about these,

drawing inspiration from the field of requirements

engineering.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is part of DEAL (Distributed Engine for

Advanced Logistics) supported as project

EETK01141 under the Dutch EET programme. For

this particular paper we are very grateful for the

contributions of Jos van Hillegersberg, Peet van

Tooren, Jan Treur, Steef van de Velde, and Pinar

Yolum.

REFERENCES

Brewer, P. C. & Speh, T. W. (2000). Using the balanced

scorecard to measure supply chain performance.

Journal of Business Logistics 21(1):75-93.

Bromley, P. (2001). A Measure of Logistics Success.

Logistics Quarterly 7(3).

Chapman, R. L., C. Soosay, Kandampully, M. (2003).

"Innovation in logistics services and the new business

model." International Journal of Physical Distribution

and Logistics Management 33(7): 630-650.

Christopher, M (1998) Logistics and Supply Chain

Management: strategies for reducing cost and

improving service 2nd Edition. Financial Times /

Prentice-Hall, London.

Christopher, M., & Towill, D. R. (2002). Developing

Market Specific Supply Chain Strategies. International

Journal of Logistics Management, 13(1): 1-14.

Donselaar, K. v., Kokke, K. and Allessie, M. (1998).

Performance measurement in the transportation and

distribution sector. International Journal of Physical

Distribution & Logistics Management 28(6): 434-450.

Fisher, M. L. (1997). What is the Right Supply Chain for

your Product? Harvard Business Review

(March/April): 105-116.

Fowkes, A. S., P. E. Firmin, et al. (2004). How Highly

Does the Freight Transport Industry Value Journey

Time Reliability - and for What Reasons?

International Journal of Logistics - Research and

Applications 7(1): 33-43.

Gibson, B. J., S. M. Rutner, et al. (2002). Shipper-carrier

partnership issues, rankings and satisfaction.

International Journal of Physical Distribution and

Logistics Management 32(8): 669-681.

Graham, T. S., dougherty, P. J., & Dudley, W. N. (1994)

The long term strategic impact of purchasing

partnerships. International Journal of Purchasing and

Materials Management, 32(4): 797-805.

Gunasekaran, A., Patel, C. and Tirtiroglu, E. (2001).

Performance measures and metrics in a supply chain

environment. International Journal of Operations &

Production Management 21(1/2): 71-87.

Hammer, M. (2001). The superefficient company.

Harvard Business Review 79(8): 82.

Ittner, C. D., & Larcker, D. F. (2003) Coming Up Short on

Nonfinancial Performance Measurement. Harvard

Business Review, 81(11): 88-96.

Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1992). The Balanced

Scorecard - Measures that Drive Performance.

Harvard Business Review 75(2): 70-79.

Kemppainen, K. and A. P. J. Vepsaelaeinen (2003).

Trends in industrial supply chains and networks.

International Journal of Physical Distribution and

Logistics Management 33(8): 701-719.

Knemeyer, A. M., Corsi, T. M., & Murphy, P. R. (2003).

Logistics outsourcing relationships: Customer

perspectives. Journal of Business Logistics, 24(1):77-

110.

Lai, K.H., Ngai, E.W.T., Cheng, T.C.E. (2004), An

empirical study of supply chain performance in

transport logistics, International Journal of

Production Economics 87: 321-331.

Lemoine, W. and L. Dagnaes (2003). Globalisation

strategies and business organisation of a network of

logistics service providers. International Journal of

Physical Distribution and Logistics Management

33(3): 209-228.

Lewis, I., Talalayevsky, A. (2000). Third-Party Logistics:

Leveraging Information Technology. Journal of

Business Logistics; 21, 2: 173-185

Lohman, C., Fortuin, L., Wouters, M. (2004). Designing a

performance measurement system: A case study.

ICEIS 2005 - ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEMS

246

European Journal of Operational Research 156:267-

286.

Menon, M.K., McGinnis, M.A., Ackerman, K.B. (1998).

Selection Criteria for Providers of Third-Party

Logistics Services: an Exploratory Study, Journal of

Business Logistics 19(1): 121-137

Mentzer, J. T. and Konrad, B. P. (1991). An efficiency /

effectiveness approach to logistics performance

analysis. Journal of Business Logistics 12(1): 33-62.

Moberg, C. R., B. D. Cutler, et al. (2002). Identifying

antecedents of information exchange within supply

chains. International Journal of Physical Distribution

and Logistics Management 32(9): 2002.

Pirttila, T., Hautaniemi, P. (1995). Activity-based costing

and distribution logistics management, International

Journal of Production Economics 41: 327-333.

Ross, A. (2002). A multi-dimensional empirical

exploration of technology investment, coordination

and firm performance. International Journal of

Physical Distribution and Logistics Management

32(7): 591-609.

Sanders, N. R. and R. Premus (2002). IT Applications in

Supply Chain Organizations: a Link between

Competitive Priorities and Organizational Benefits.

Journal of Business Logistics 23(1): 65-83.

Sink, H. L., Langley Jr., C. J., & Gibson, B. J.(1996).

Buyer observations of the US third-party logistics

market. International Journal of Physical Distribution

& Logistics Management, 26(3): 38-46.

SCOR (2003); Supply-Chain Operations Reference Model

– SCOR Version 6.0; April 2003.

Stank, T. P., Goldsby, T. J., et al. (2003). Logistics service

performance: estimating its influence on market share.

Journal of Business Logistics 24(1): 27-55.

Stewart, E. (1995) Supply chain performance

benchmarking study reveals keys to supply chain

excellence, Logistics Information Management, 8(2):

38-44.

Themido, I., Arantes, A., Fernandes, C., Guedes, A.P.

(2000). Logistics costs case study – an ABC approach,

Journal of the Operational Research Society 51:1148-

1157.

Toni, A. D., Nissimbeni, G., & Tonchia, S. (1994). New

trends in supply environment. Logistics Information

Management, 7(4): 41-50.

Vaidyanathan, G. (2005). A Framework for Evaluating

Third-Party Logistics, Communications of the ACM,

January 2005 48, 1: 89-94

Weber, M. M. (2002). Measuring supply chain agility in

the virtual organization. International Journal of

Physical Distribution and Logistics Management

32(7): 557-590.

PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT AND CONTROL IN LOGISTICS SERVICE PROVIDING

247