APPLYING SDBC IN THE CULTURAL-HERITAGE SECTOR

Boris Shishkov

Department of Computer Science, University of Twente, 5 Drienerlolaan, Enschede, The Netherlands

Jan L.G. Dietz

Department of Software Technology, Delft University of Technology, 4 Mekelweg, Delft, The Netherlands

Keywords: SDBC; Software broker; Cultural heritage

Abstract: An actual cultural-heritage-related problem is how to effectively manage the global distribution of digitized

cultural and scientific information, taking into account that such a global distribution is only doable through

the Internet. Hence, adequately designing software applications realizing brokerage functionality in the

global space, particularly concerning digitized cultural/scientific information, is to be considered as an

essential cultural-heritage-related task. However, due to its great complexity, the usage of the existing

popular modelling instrumentarium seems insufficiently useful; this is mainly because the realization of a

satisfactory cultural-heritage brokering requires a deep understanding and consideration of the original

business reality. Inspired by this challenge, we have aimed at exploring relevant strengths of the SDBC

approach which is currently being developed. SDBC’s being capable of properly aligning business process

modelling and software specification, allowing for re-use and being consistent with the latest software

design standards, are among the facts in support of the claim that SDBC could bring value concerning the

design of cultural-heritage-related brokerage applications. Hence, in this paper we motivate and illustrate

the usefulness of SDBC for the cultural-heritage sector.

1 INTRODUCTION

The latest ICT (Information and Communication

T

echnology) developments could bring numerous

societal benefits, among which is the possibility for

a global access to cultural/scientific manuscripts

located at any place. The actuality of this issue could

be seen from a number of (currently progressing)

culture-heritage-related projects, such as the project

DigiCult (DigiCult, 2004). According to such

projects (to most of them), several types of activities

are observed, concerning the digitization of cultural

and scientific heritage, among which are:

• the classification of existing cultural heritage

materials;

• the recognition and processing of images from

such materials;

• the specification and maintenance of the

metadata related to digitized materials;

• the management and distribution of the

digitized cultural/scientific materials.

In the current paper, we report further studies

related to the last of the above mentioned issues. A

previous study (Shishkov, 2004) has started the

exploration of the strengths of SDBC concerning

this particular cultural-heritage-related problem.

As stated in the above-mentioned study, in tune

with the current technological possibilities and user

demands, such management and distribution (of

digitized cultural materials) is to be considered in

global respect. It is essential that the digitized

cultural/scientific materials are globally available to

the public. Next to that, their accessibility must be

adequately regulated, which adds complexity: some

materials are to be accessible freely by anyone,

others should be accessible only by authorized users,

still others are to be distributed commercially, and so

on. Thus, an advanced brokerage functionality needs

to be realized in this regard. As far as the ‘global

information space’ is concerned, this job is to be

done by a software broker. By ‘software broker’ it is

meant a software application which realizes a

brokerage functionality. As it is well-known,

software brokers are built and used for a number of

purposes, for instance, flight/accommodation

reservations, e-Business, Tele-Work, and so on.

394

Shishkov B. and L.G. Dietz J. (2005).

APPLYING SDBC IN THE CULTURAL-HERITAGE SECTOR.

In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, pages 394-398

DOI: 10.5220/0002513603940398

Copyright

c

SciTePress

However, a global management and distribution of

digitized cultural (and scientific) data, which is

characterized by a number of restrictions (as

mentioned above), makes the brokerage task more

complex than what is usually observed in brokerage

systems. It is essential, therefore, specifying such a

(software) brokerage system, based on a sound

consideration of the original business system, to be

supported by it. This leads to a more general actual

research problem, namely the alignment between

business process modelling and software

specification.

The SDBC (SDBC stands for S

oftware Derived

from B

usiness Components) approach has been

introduced (Shishkov & Dietz, 2004-1; Shishkov &

Dietz, 2004-2) and considered also in another paper

from the current Proceedings, as an approach being

capable of adequately addressing the business-

software alignment by considering ‘logical’

components that represent the logical building

blocks of a software system. In particular, the

approach allows for deriving pure business process

models (called business coMponents) and reflecting

them in conceptual (UML-driven) software

specification models (called software coMponents).

In the business coMponent identification, SDBC

follows a multi-aspect business perspective,

guaranteeing completeness. In the business

coMponent – software coMponent mapping, SDBC

follows rigorous rules, guaranteeing adequate

alignment. Being UML-driven, SDBC is in tune

with the current software design standards.

The aim of this paper is to add further evidence

in support of the claim that the (SDBC) approach

could be useful with regard to the cultural-heritage

sector. The paper uses and further considers the

example presented in (Shishkov, 2004).

The paper’s outline is as follows: Section 2

considers relevant cultural-heritage information.

Section 3 illustrates the application of SDBC, using

a small example. Section 4 contains the conclusions.

2 THE CULTURAL HERITAGE

SECTOR

Among the institutions (in most countries) which are

mainly concerned with the cultural heritage issue are

the archival, library, and museum institutions. Such

is the case in The Netherlands, for instance, where

these institutions take part in the specification of the

Dutch national long-term cultural strategy,

addressing the cultural-heritage-related issues (it is

called in The Netherlands, Cultuurnota

(http://www.cultuurnota.nl)). The situation in other

countries (such as Bulgaria, for example) is similar.

In the majority of the national cultural strategies the

actuality of the cultural heritage issue is recognized,

and especially the need to allow the cultural heritage

sector adequately benefit from the current technical

and technological possibilities. That is why more

and more (EU) projects appear, addressing cultural-

heritage-related problems. An example of such a

project is the DigiCult project (DigiCult, 2004). It is

claimed (not only within this mentioned project) that

the mere existence of technical and technological

possibilities does not mean that they are

straightforwardly utilizable, particularly in such a

specific domain. What is required is that a clear

perception of the original business (cultural heritage)

is reflected in the technical/technological

consideration. Otherwise, the (technical) support

realized would only partially reflect the original

requirements and its effect would be much limited.

There are many examples for such partially

successful cultural-heritage-related initiatives, such

as the project American Memory

(http://memory.loc.gov); it has delivered a digital

collection of cultural materials. A gateway has been

built to rich primary source materials relating to the

history and culture of the United States of America.

Through the web site of the project, one could

access more than 7 million digital items from more

than 100 historical collections. However, the project

has not considered at all how the realized system

could handle complex situations, such as dealing

with different access levels. The project has not

considered as well how such kind of system could be

built for other analogous purposes and how it could

operate in the context of a global cultural-heritage-

brokering environment.

It is agreed in the cultural heritage community

that a way to bring improvements in this direction is

to succeed in designing (cultural-heritage-related)

software systems which are soundly rooted in an

adequate model of the original business reality.

Thus, taking into account that:

1. most of the current popular software design

methods are insufficiently capable of adequately

aligning business process modelling and software

specification; and

2. there is an approach proposed, namely the SDBC

approach, which is reflecting this particular problem,

we have been inspired to explore some strengths of

SDBC, relevant to the cultural heritage sector.

In the following section, we will present and

partially illustrate our view on applying SDBC for

solving some cultural-heritage-related problems.

APPLYING SDBC IN THE CULTURAL-HERITAGE SECTOR

395

3 APPLYING SDBC

Offering useful advantages concerning the

specification of software systems intended to

support complex business systems in different

domains, the SDBC approach has been applied

successfully in test cases concerning the domains of

e-Business and Tele-Work. It has been demonstrated

how (using SDBC) a software brokerage system

could be specified. As it is well known, software

brokers are currently of great interest because of

their wide applicability resulting from their actual

(brokerage) functionality. They usually facilitate

(Shishkov, 2004): the match-making of globally

available information; the management of digital

archives; the globalization of used data networks.

Through software brokers, users could have a quick

and effective match-making at low costs.

Because of the relevance of software brokers to

the (discussed above) cultural-heritage-related

problem, SDBC is applied (as an approach which

possesses strengths concerning the business-

software alignment in general and the specification

of software brokers, in particular) in building a

cultural-heritage-sector (software) broker being able

to effectively handle the management and global

distribution of metadata as well as of digitized

cultural/scientific information. Such a broker is to be

usable on a global scale through the Internet.

In this way SDBC would stimulate the global

availability of cultural/scientific information.

The particular role of SDBC in building such

brokers will be only partially illustrated below,

because of the limited scope of this paper. Because

of the same reason, just the essential issues will be

mentioned. And also, no explanations will be offered

concerning the modelling techniques used. Such

explanations are to be found in the SDBC sources

which were mentioned before.

We first consider the cultural-heritage brokerage

system-to-be very generally: we could view such a

system as consisting of a number of ‘sellers’

(distributors) of anything and a number of ‘buyers’.

If we consider a general broker, it should match

appropriate seller and buyer information based on

some criteria.

A further analysis should follow, based on this

general view, considering the particular cultural

heritage information (discussed already). In SDBC,

the results of such an analysis are reflected in the

SCI model (interested readers could read of the SCI

model in the SDBC materials).

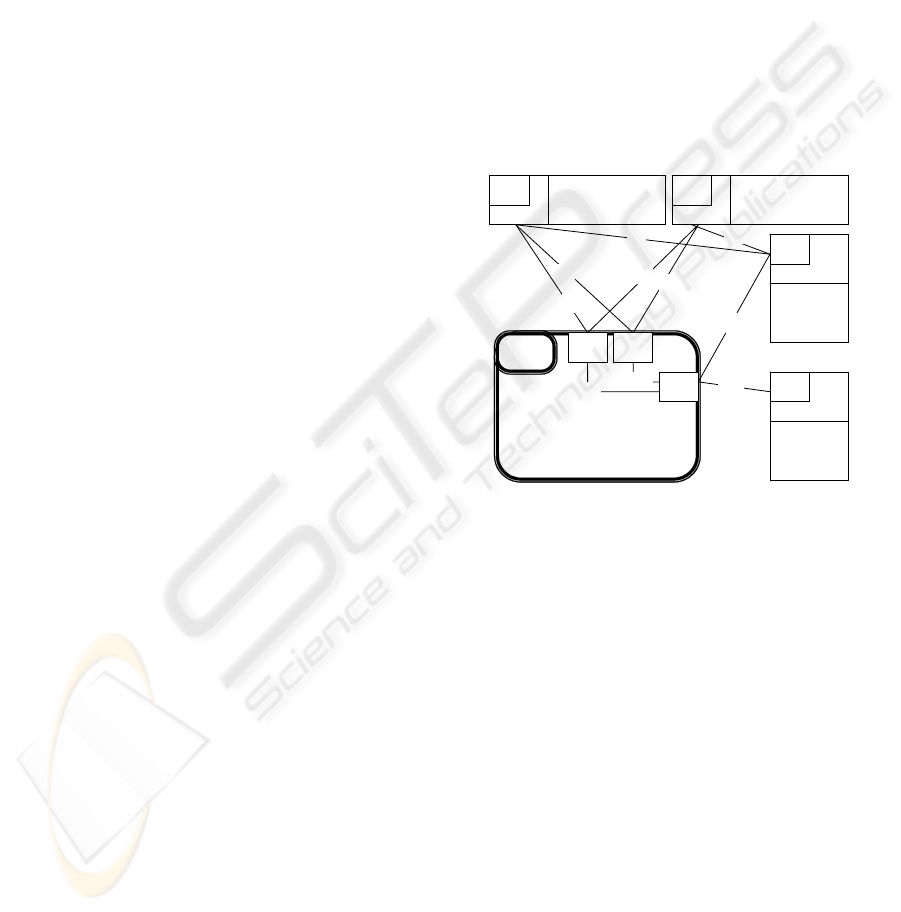

The general SCI model relevant to the current

situation is depicted, just for illustrative purpose, in

Figure 1. The model is incomplete, only some basic

issues are there. Among them are: units within the

General Broker (AU (Acceptance Unit): responsible

for accepting and handling submissions from sellers

and buyers; FU (Financial Unit): responsible for

handling the fee payments done by sellers/buyers as

a compensation for the work of the broker; MM

(Match-Maker): responsible for performing the

match-making concerning the seller and buyer

information) and actors outside the General Broker

(Seller: offering/distributing something, for

example, digitized cultural materials; Buyer: being

interested in something, for example, in particular

digitized cultural materials; Expert: responsible for

assisting the broker in some complex situations (in

which, for example, ‘human’ cultural heritage

experience is required); Insurer: responsible for the

insurance of relevant issues, for instance, insurance

against fraud).

GB

MM

FU

A

U

Selle

r

S

E

Expert

I

Insurer

1 3

2

1 0

8

5

7

4

6

Buyer

B

9

Figure 1: The General Broker (GB): SCI Model.

Hence, the GB SCI model facilitates the structuring

of the initial case information to be reflected in the

identification of a business coMponent.

In this particular case, it is suggested that a

general business coMponent is identified. The

reason relates to the wide usage of software brokers

in a number of cases; thus, identifying a general

model would allow for re-using it many times. Our

(DEMO-based) general business coMponent is

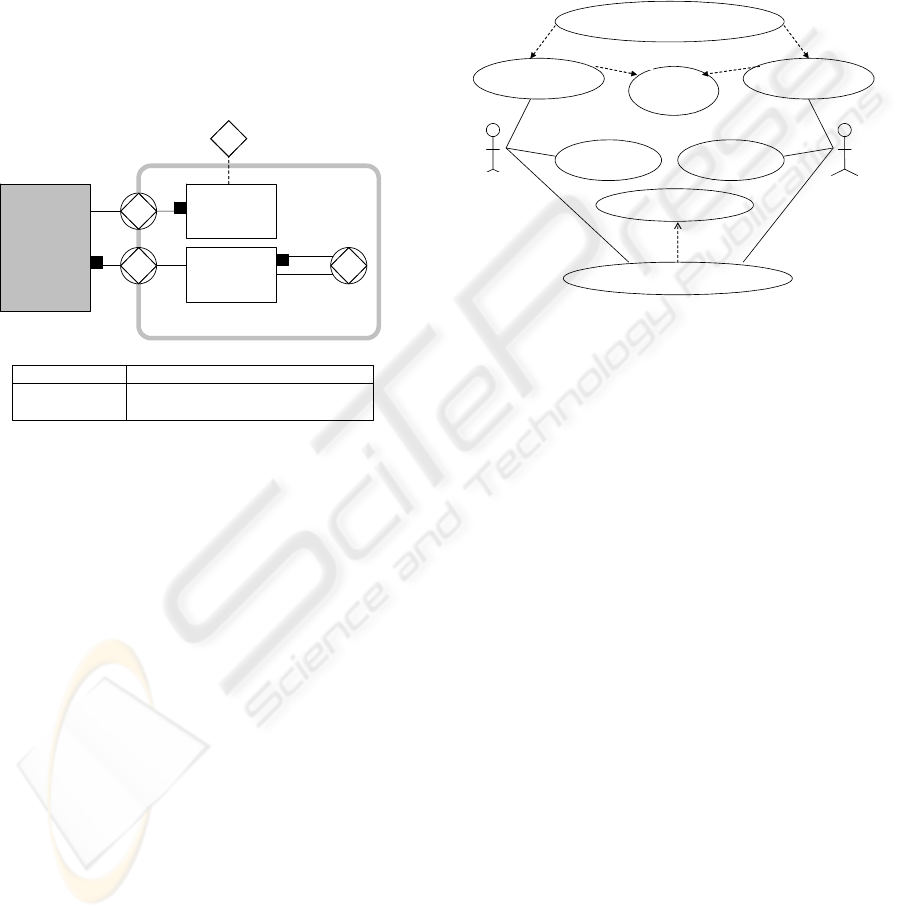

depicted in Figure 2. The model is incomplete

because of its having just an illustrative purpose.

More information on the DEMO modelling and the

derivation of a DEMO model within SDBC could be

found in the SDBC materials, mentioned before.

As seen from the Figure, two internal GB actors

(actor-roles) are depicted and also two external

actors (‘seller’ and ‘buyer’: they are modeled as an

aggregated actor because of their having the same

general attitude towards the broker). As for the

internal GB actors depicted, they are the match-

ICEIS 2005 - INFORMATION SYSTEMS ANALYSIS AND SPECIFICATION

396

making unit (‘match-maker’) and the financial unit

(‘payment controller’). Two transactions are

specified, concerning all the mentioned actors: T01

match-making (executed by the match-maker) and

T02 payment (executed by seller/buyer). One

transaction is specified, taking place within the GB:

C3 (it concerns the periodical self-activation of the

payment controller in handling all the payments

related to a particular period of time). There is also a

data bank depicted (EB01), containing the necessary

data (concerning both buyers and sellers) that the

match-maker should have in order to be able to

realize a match-making.

A01

match-

maker

T01

T02

S02

buyer

/

seller

buyer/seller

data

transaction type resulting fact type

T01 match-making

T02 payment

F01 match <M> is made

F02 the fee for period <P> by <S/B> is paid

A01

payment

controller

C3

EB01

Figure 2: DEMO-based (GB) general business component.

Once built, this general business coMponent needs

to be extended, according to SDBC, aiming at the

identification of a particular business coMponent, in

this case: Cultural heritage sector broker (built again

with the DEMO notations). However, because of the

limited scope of this paper, the transformation from

the general business coMponent (The General

Broker) to the particular business coMponent (The

Cultural heritage sector Broker) is not presented.

Information on how such an extension is carried out

within SDBC could be found in the (mentioned)

SDBC materials.

According to SDBC, a DEMO-based business

coMponent (The Cultural heritage sector Broker)

should be reflected in a use case software

specification model. An example of such a model is

depicted in Figure3. The model is incomplete,

containing only some of the use cases characterizing

such a broker. The broker is to use a database. It is

virtually divided in two parts: one concerning the

data submitted by distributors (of digitized cultural

heritage materials) and the other one, concerning the

data submitted by users. They are represented on the

Figure by ‘DBD’ and ‘DBU’, respectively (‘DB’

standing for database; D(U) standing for distributor

(user)). On the Figure, it is just illustrated how a

software specification model would look like. The

use case model will not be explained since it is

expected that most of the readers are familiar with

UML. As for the DEMO – use case derivation

mechanism, information on it could be found in

(Shishkov & Dietz, 2004-3).

User

Distributor

<<include>>

Perform Match

-

making

Check Data Accuracy

Remove Data

from DBD

Remove Data

from DBU

Request Additional

Information

Check

user’s info

<<include>

>

<<include>>

Add Data in DBD Add Data in DBU

<<extends>>

<<extends>>

Figure 3: The Cultural-heritage-sector broker: use case

software specification model.

4 CONCLUSIONS

This paper has provided further evidence on the

practical applicability of the SDBC approach, by

considering its usefulness for the cultural heritage

sector. In this way, the paper complements the other

SDBC-related paper within the current Proceedings.

Among the further research goals of the authors

is the generalization of the results concerning the

usage of SDBC for specifying brokerage systems in

different domains, including Cultural heritage, e-

Business and Tele-Work. This would not only bring

further evidence about the values of SDBC

concerning software specification but would also

result in a deliverable (a thorough general brokerage

model) which is helpful for developing useful

software products. To realize this, it is essential to

complement the general brokerage model with

rigorous rules on how to extend it depending on the

particular purpose of use. The existing examples

(within the mentioned domains) are to be considered

as appropriately complementing such rules. The

rules themselves would be defined based on the

general SDBC application guidelines (Shishkov &

Dietz, 2004-1; Shishkov & Dietz, 2004-2).

However, generalizing further, towards SDBC

models which are general for any domain and

concerning any functionality, would add little value

APPLYING SDBC IN THE CULTURAL-HERITAGE SECTOR

397

mainly because the extension of such models would

require significant efforts. Therefore, we look

towards functionality/domain-specific general

business coMponents through which SDBC could

adequately accomplish business-software alignment

and proper re-use. Otherwise said, we envision a real

re-use value of applying SDBC:

- either if it grasps the core of a functionality, to

be reflected in different domains;

- or if it captures essential issues for a domain,

allowing for further specializations depending on the

particular needs.

It is expected that these and further SDBC-

related (research) achievements would be greatly

useful for the current service development which has

significant societal relevance (Pires et al, 2003).

SDBC could facilitate the specification of services

not only by providing business-software-alignment

and re-use mechanisms but also through a support

towards the grasping of the context concerning the

services’ operation. Taking into account that such a

context grasping requires a sound business

modelling and its further adequate reflection in a

(service) specification, it is logical to expect that

SDBC (itself developed around such desired

properties) might be helpful.

Therefore, the essential values of the SDBC

approach, namely adequate business modelling,

proper business-software alignment, and re-use, do

prove to be relevant both scientifically and

societally.

REFERENCES

DigiCult, 2004:

http://slim.emporia.edu/globenet/sofia2004/index.htm

Pires, L. F.; M. van Sinderen, C. de Farias, J.P.A.

Almeida. Use of models and modelling techniques for

service development. In I3E’03, 3

rd

IFIP Confeence on

E-commerce, E-business, and E-government. Kluwer

Academic Publishers, 2003.

Shishkov, B. Designing cultural heritage sector brokers

using SDBC. In International Journal “Information

Theories & Applications” (IJ ITA), Vol. 10, 2004.

Shishkov, B. and J.L.G. Dietz, 2004-1. Aligning business

process modelling and software specification in a

component-based way, the advantages of SDBC. In

ICEIS’04, 6th International Conference on Enterprise

Information Systems. ICEIS Press, 2004.

Shishkov, B. and J.L.G. Dietz, 2004-2. Design of software

applications using generic business components. In

HICSS’04, 37th Hawaii International Conference on

System Sciences. IEEE Computer Society Press, 2004.

Shishkov, B. and J.L.G. Dietz, 2004-3. Deriving use cases

from business processes, the advantages of DEMO.

Enterprise Information Systems V, Edited by O.

Camp, JB.L. Filipe, S. Hammoudi, and M. Piattini,

Kluwer Academic Publishers,

Dordrecht/Boston/London, 2004.

ICEIS 2005 - INFORMATION SYSTEMS ANALYSIS AND SPECIFICATION

398